Andrew Mehrtens stood out as a prince of the game - and also one of its jesters.

His skills were sublime, obviously. Crowds thrilled as much to his prodigious punting and the sweet-timing of his goalkicking as they did to his uncanny eye for an attacking opportunity, acceleration through a gap or pinpoint pass to put his outsides into space.

Yet he carried his gifts so lightly, or at least gave the appearance of doing so, looking almost casual as he peeled off another 60m touchfinder or nailed a matchwinning placekick.

Pick your top 20 greatest All Blacks of all time.

That lighthearted streak and obvious love of the game helped to win him legions of fans, even in parts of the country where Cantabrian rugby players aren't typically embraced as heroes.

Maybe that's because he defied the Canterbury stereotypes, departed so markedly from the image of gruff, taciturn hard-men established by some previous leading lights of that province.

On-field, he would shrug and chuckle between plays or remonstrate with referees or line umpires who gave less credit for one of his booming touchfinders than he thought was due. Off-field he was that rarity - a player whose pre-game or post-match comments were worth listening to.

With a microphone in his face "Mehrts" was a cliche-free zone, dissecting games with wit and intelligence and sometimes startling interviewers with the unpredictability of his responses.

Mehrtens arrived on the scene just when New Zealand rugby needed him. After Grant Fox retired in 1993, Laurie Mains and his fellow selectors had struggled to find a first five-eighths. Marc Ellis, Simon Mannix and Stephen Bachop were all tried and found wanting.

Then, in 1994, a buzz began about a youngster from Canterbury who seemed blessed with all the skills and a big-match temperament to go with it. Helping Canterbury to win the Ranfurly Shield that year - and defend it, thanks to his nerveless goalkicking - Mehrtens announced himself as a genuine prospect.

By the next year the boyish 21-year-old forced his way into the All Black squad, scoring 28 points on his test debut against Canada. Suddenly, with that critical last piece of the jigsaw in place, Mains' team began to look worthy challengers for the 1995 World Cup.

With mobile ball-winning forwards and the supreme attacking potency of Jonah Lomu and Jeff Wilson out wide, the scene was set for Mehrtens to orchestrate something special. He obliged, repeatedly unleashing the side's strike-weapons with his trademark cut-out passes.

One pass sparked the move that led to Lomu steamrollering a try against England, though Mehrtens characteristically found the humour in being congratulated about it. "All Jonah had to do was run nearly 60m and beat four or five tacklers," he deadpanned.

Sadly, Mehrtens' wonderful rise was interrupted by the fufilment of another fairytale - that of a World Cup win for post-apartheid South Africa. In the final he missed an extra-time drop goal.

He recovered from that disappointment to take his place in many successful All Black teams over the next nine years, though his international career was interrupted both by injuries and by the tendency of All Black coaches to prefer at times the talents of his great rival Carlos Spencer.

In retrospect, it seems hard to fathom how a player of Mehrtens' pedigree wasn't a fixture, when uninjured. Partly it was because his slender frame wasn't ideally suited to the defensive and "taking-it-to-the-line" requirements of the professional game.

And not every coach was as big a fan as Laurie Mains. Mehrtens had his ups and downs with Robbie Deans at the Crusaders and John Hart often preferred Spencer. Hart once outraged Mehrtens fans by appearing to blame him publicly for a 1998 defeat by Australia.

In a Super 12 final, Deans once preferred the journeyman Cameron McIntyre, leaving Mehrtens on the bench - a bit like driving a Familia when you've got a Rolls-Royce in the garage.

But if reflection on his career is tempered by regret at what might have been, Mehrtens' record remains outstanding by any measure. By the time he left to play in the Northern Hemisphere in 2005 he had amassed an international 967 points in 70 tests, which puts him second only to Daniel Carter on the all-time points-scoring list.

And those tests included numerous wonderful exhibitions of his skill, such as that fondly remembered double-round with Frank Bunce to lay on the winning try in the test against Australia in Brisbane in 1996, a classic example of his pace and eye for opportunity.

Mehrtens played tennis to a high level as a teenager and sometimes, at his best, made a rugby pitch feel like a tennis court, dominating the space with raking cross-court winners and pinpoint drives down the line. He detected his opponents' weaknesses and had the skills to take merciless advantage.

And if his confidence sometimes meant Mehrtens had a kick charged down or failed to find touch with an over-ambitious punt, his fans were ready to accept it as part of the package.

Pick your top 20 greatest All Blacks of all time.

Next Monday nzherald.co.nz will compare our experts' list with the public's.

Andrew Mehrtens - Prince among players

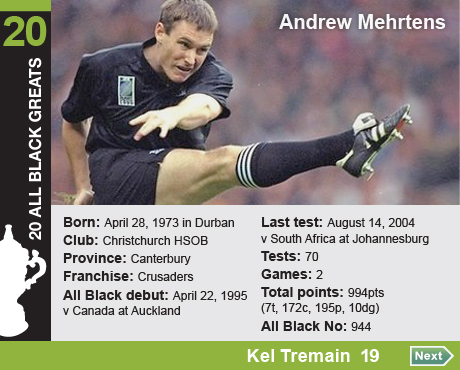

Andrew Mehrtens converts a penalty against France in 2000. Photo / Getty Images

AdvertisementAdvertise with NZME.