Through the Yard Glass

A journey into rugby heartland

Here is what I know to be true: Strathmore beat Toko 53-3 on a sun-soaked May day to retain the Dean Cup.

It is also true that they do so courtesy of defeating, a fortnight earlier, Whangamomona at the same ground, the Toko Domain, 35-12.

The trophy, the oldest challenge cup in New Zealand, has made the short journey back from the domain to the Toko Junction Tavern. There it will sit proudly on the top shelf of a corner dedicated to local sport, guarded by the boars’ heads that stare glassy-eyed from the walls.

The rugby men of Strathmore do not take the Dean Cup home with them because, well, there’s nowhere to take it. Most of the players no longer live in the valley, there is no rugby field, no clubrooms, the district hall is long gone and Strathmore is nothing more than a T-junction with the Coulton farm house and cowshed alongside.

This is true. I have been there and seen it.

Despite these demographic hurdles, Strathmore, who looked sharp in Persil-white and green hoops and matching shorts and socks, were vastly superior to the rugby men of Toko, who were hamstrung by late, unsatisfactory withdrawals. Toko, in yellow and black hoops, were an eclectic bunch from the waist down, with shorts and socks representing a wide range of the colour spectrum.

Strathmore scored nine tries to Toko’s single penalty and dominated from tighthead to fullback.

This I also know to be correct.

This is what I can’t be sure about, but nevertheless hold to be true: the Dean Cup used to be about rugby and for 80 minutes still retains that veneer, but scratch the surface and it represents something far more fundamental – a way of life that is literally disappearing.

Played between three isolated valleys in the back blocks of Taranaki’s eastern hill country, the cup remains a tenuous touchstone for the families who carve out a mostly dry-stock living here.

“It’s gully against gully. It’s the people of the district getting together for a game of rugby,” says 64-year-old Tutatawa farmer, Strathmore chairman and former Toko player-coach John McBride.

“It’s highly passionate. There’s blood lost,” he pauses, “but nothing too serious of course.”

This isn’t the most polished rugby, but it’s willing. Self-policing is acknowledged as an important factor in the Dean Cup’s ecosystem and there is a tacit understanding that rucking is tolerated. The post-match sting of soapy hot water into red-raw furrows is expected.

A drink will be shared with the man who inflicted the damage. Their wives will laugh about it out the back where the mutton is being carved up, where buttered bread and spuds are king and salads are garnish. Their kids will run around together as the last of the natural light disappears behind the big mountain to the west.

This is country rugby, yes, but it’s a social network built upon actual human interaction. That connection is vital in maintaining relationships between families that have had little choice but to leave their farms and leave the district. It lubricates the relationships of those few who have stayed. It’s their way, too, of recognising the efforts of their ancestors who created these homesteads and family trees in such inhospitable terrain.

If those sound like are old-world concepts, then rest assured this is an old-world kind of place and the Dean Cup is an old-world kind of happening and, if you really want to get to the crux, the old world faces an uncertain future.

The truth is that this, not the rugby, is the real story of the Dean Cup.

Unfurl a map of the North Island, find Stratford just to the east of Mt Taranaki and travel about 10km on State Highway 43 to Toko, where the fertile volcanic ringplain that fuels the dairy industry ends.

It’s been an easy journey so far, but to get to the genesis of this story you have to have your wits about you as the road pinches in from the sides as you climb up and over the Strathmore, Pohokura and Whangamomona saddles.

The Whangamomona Hotel is marketed as the most isolated pub in the country and it feels that way. It was here in 1907 that publican Athalinda Dean – a formidable woman of extravagant tastes – bought and donated a cup to be played between the cricketers of the Whangamomona village and those who farmed farther down the valley.

The enterprise was an abject failure.

Carving a playable cricket field from the rugged, sodden country was a task too far. The magnificent trophy, which was thought to have cost Dean upwards of £20, was instead donated to the local rugby club, who opened it up to challenges from Strathmore, Toko and Ohura (who dropped out after a few successful years).

The trophy became a source of pride for the three districts. In the early days, when roads resembled a ribbon of mud, challenges could be three-day affairs: one day to get there; one to play and drink; one long, long day to return.

The host team would open up their village hall for the festivities. A band would play, sawdust would be spread on the floor to soak up the alcohol and everybody within driving distance would join the party.

“My earliest memories are of being dragged around the hall on sacks the next morning. It was how we cleaned up,” says Carrol Coulton, whose family has farmed the Strathmore Valley for generations.

Coulton played his first Dean Cup match for Strathmore while still at high school.

“Oh hell yes. Beat Whanga at Whanga. I learned to drink beer that day too. It wasn’t pretty,” he says.

Coulton takes his name from his grandfather, Private Carrol Coulton, whose name is inscribed on the lonely Strathmore and Te Wera Makahu Districts cenotaph, one of 25 men from the district to perish in World War I. Another 25 would die in World War II.

It’s a staggeringly high body count, but in the post-war era a different sort of attrition took hold.

“There’d be no more than 50 people living here now,” says Coulton. “The local school, Huiakama, used to have about 50 kids, it might have 15 now. Other schools in the area have closed.

“It’s all the farm amalgamations,” Coulton says. “The area is totally depopulated.”

Back in the day every farm would have about six people working it. Those little farms are now big farms.

“I’m guilty of it. I bought out one neighbour, bought half of another one. It’s the economics of scale.”

The Coulton name will live on in the valley. His son Michael will inherit the land when Carrol shuffles off. He’ll be the fifth generation of Coultons on the same land. Michael’s son, the family anticipates, will be the sixth.

The hall is gone, though. It might not have been a picture to look at, and stood unused for most of the year, but take away an area hall and you’re taking away its heart. Inside it had matai floors, rimu studs. Someone paid $5000 to come and take the hall so they could strip out the timber.

The hall was the meeting place for the Strathmore Women’s Division, but that had folded, as had the bowls club and the euchre evenings. Even the Bachelors Ball, once the social highlight of the season – “men had to pay, women were free” – had ceased to exist. The Dean Cup festivities had long moved down the road to Toko.

The hall fell into disrepair. Nobody wanted to fund an unused space, no matter how pretty the floor was.

The hall in Whangamomona has survived, just, as have a few of the historic buildings, which were once destined to decay. All have plaques and all tell the same lament: of the hall, general store, post office, butcher and bakery that were once part of a thriving settlement until farming and forestry technology changed. The post office stopped being viable and, eventually, the trains that served the Stratford to Ohurakura line stopped coming as well.

“We once had three schools in the area serving 120 kids,” says Richard Pratt, the publican following in the footsteps of Mrs Dean. “Now we have one school [Marco] with about 15 kids.”

There are, he reckons, about 120 people left in the Whangamomona Valley. Curious tourists that trickle down the Forgotten World Highway, or on the converted golf carts that are the only vehicles left on the rail line, keep the pub alive but outside beer and a bed, any other form of retail has long been an exercise in futility.

These are the least densely populated districts in Taranaki and by extrapolation some of the least populated areas of the country. Yet when the weather rolls in and settles, as it so often does, it can feel claustrophobic, like you’re on the set of a Vincent Ward film.

Winters start early and finish late. They are invariably wet. The pay-off for all that water is grass.

Grass is good. Grass feeds the sheep and the cows. In the old days, there weren’t many cows. Of the many documents you can find via Google, they don’t come much more arcane than the Annual Sheep Returns, but via this wonderful resource I can tell you that in 1928 there were 80,975 sheep in Whangamomona, up 5541 on the previous year.

Sheep were serious business. Not only was the meat valued but so was the wool. The bottom has dropped out of the wool market though, to the point where, McBride says, some sheep and beef farmers are choosing just to run cattle.

“Wool is a struggle,” he says. “You might just cover the costs of taking it off their backs.”

“Just,” says someone walking by who overhears the conversation.

When the margins on primary produce were higher, smaller farms were viable. Smaller farms meant more people in the district. More people meant more services were required. More services meant more people.

That’s how it always worked… until it no longer did.

And they, the remaining people of the eastern districts of Taranaki, saw all this happening in plain sight. It wasn’t a slow, incremental boiling-the-frog scenario.

The depopulation happened quickly. The erosion of their communities and lifestyles went with it and they couldn’t do a thing about it.

By rights, the Dean Cup should have gone – along with the euchre club and the bowls clubs and the women’s division and the Bachelors Ball. But somehow it remained and that mere act of survival, of defiance, is the best reason anyone can think of to keep it going.

“We raged. Raged against the dying of the light,” says Toko No 8 Richard Cook.

With a six-foot-plenty frame, a bushman’s beard and boots that look built for trouble, Cook doesn’t appear like a natural bard.

Quart bottle of affordable beer in hand, leaning against a toilet block at the back of the Toko clubrooms – the same toilet block where last year two dead and rapidly decomposing sheep had to be removed before a game – Cook is looking for ways to explain the bravery of his undermanned team’s performance.

He chose the aforementioned verse.

“That’s poetry,” he tells a bemused teammate. “That’s bloody Bernard Kipling, mate.”

Cook is a loquacious emblem of the modern Dean Cup. He lives in Wellington, where he works in forestry logistics, and no longer laces up his boots on a Saturday.

“I moved away about, shit, 20 years ago, but this is important. My family has been down the Raupuha Rd for 102 years, the Dean Cup has been there just a little bit longer than that.

“It’s a bit of a liquid lubricator to be honest. It’s a great chance to gather together and tell stories. It’s not always easy farming, there’s not a lot of rural support out there, people looking out for each other. This, while it’s a festival and spectacle of rugby, is also a great chance for the locals to come down and interact and get a bit ratty later on.”

You can’t ignore the fact that alcohol plays a big part in proceedings. You can’t deny the fact, also, that attitudes to, and more specifically policing of, drink-driving laws has torn away at the social tissue that connected rural rugby clubs to the wider community.

During the centenary celebrations, Dean Cup stalwart David Walter wrote: “In earlier days the drinking ritual was manly and mandatory, smoking was almost compulsory and drink-driving was a highly recommended activity. Panelbeaters got quite a surge of winter activity following a Dean Cup challenge.”

Beer is the amniotic fluid that provides clubs with financial nutrition. The first tryscorer in all Dean Cup matches – in this case Strathmore captain Simon Edwards – is expected to down a yard glass.

He does, slightly haltingly, but impressively enough to win a few hard-earned slaps on the back.

The fatty meat and carbs will soak up some of it, but someone will need to drive Edwards home tonight.

So how does a region that numbers in the hundreds, manage to turn out three teams of between 20-25 players?

Toko still have enough players to call on to maintain a Saturday club side, but it is patently obvious that Strathmore and Whangamomona do not have the permanent or even transient population – shearers, fencers and forestry workers mainly – to make this feasible.

To ensure Athalinda Dean’s magnificent gift keeps giving, they have had to get creative.

Whereas in the past you had to have lived or worked in one of the three areas, now you can call in family ties.

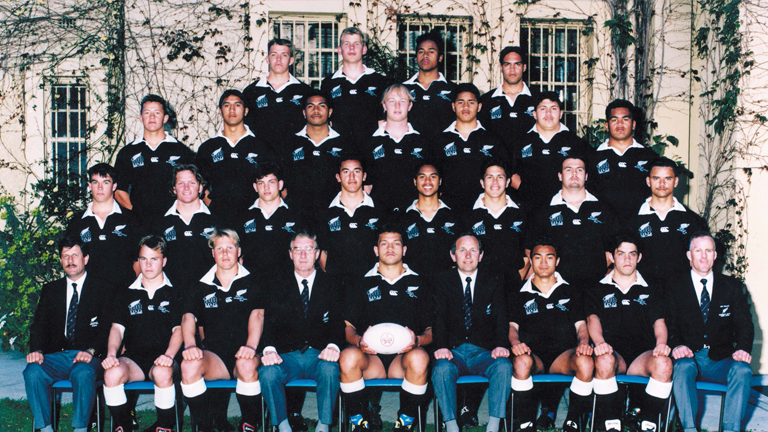

The “marriage rule” has become a boon to playing stocks, with professional-era All Blacks Gordon Slater (Strathmore) and Mark “Bull” Allen (Whangamomona) famously – around these parts anyway – facing off against each other in a match that was played at Rugby Park, New Plymouth.

Slater now farms within the Toko boundaries but his allegiance remains, no doubt for the sake of his marriage, to Strathmore.

On this weekend, Strathmore also sported a strapping Fijian lock, George Rova. He qualified through marriage to Sonia after the two met in neutral territory – the infamous Walkabout pub in west London’s Shepherd’s Bush.

“We’ve included spouses and people involved with family just to make sure we get the 20-25 guys per team so we can keep going,” McBride says.

He first played for Toko in 1973. He was player-coach there before switching allegiance to Strathmore when he bought a farm in that valley a few years later. He remained involved in the Toko Saturday side and is a life member of both clubs.

He also has to take a firm line with the premier division Saturday clubs, who don’t necessarily approve of several of their senior players getting injured, or drunk, on a Sunday.

“They’re our sons,” McBride says. “While the clubs, especially [nearby] Stratford, give us a little bit of gyp about their players getting injured, they could fall out of bed and get injured too. The way we look at it we lend them our sons on a Saturday and they send them back battered and bruised.

“We need our sons to support us and play the game.”

More than once it was heard that Strathmore had been much more active in their recruitment, but it was said more in admiration than admonishment. On this day, four grandsons of Strathmore nonagenarian Don Hopkirk laced up: Fletcher Burnett, Tadhg McColl, Connor McColl and Sean McColl.

Arguments about eligibility, most of them good-natured, some not, have stretched back for generations.

To mediate in boundary disputes, a Three-Wise-Men committee has been formed, involving one person from each valley.

“The Douglas Rd divides Strathmore and Toko,” McBride says. “A few years back we poached one of the Toko players because his farm wrapped around the end of the road. We had to relent in the end because his house was in Toko.”

Former All Black lock Alan Smith, uncle of Conrad, recalled in the centenary booklet the time when he received a letter from the Strathmore selection committee insisting he must change his allegiance from Toko. He had moved from one side of Douglas Rd to the other.

He refused Strathmore’s entreaties and, incidentally, never missed a game unless he had representative commitments.

Other All Blacks to have played, it is believed, are Jack Sullivan and Bob “Barefoot” Scott, who both spent time at Tangarakau, a ghost town just north of Whangamomona that was once a large railway camp.

There were no All Blacks on this occasion. At one stage, when Toko gathered at the pub for a pre-match meeting, it looked like there might not be a match at all, with the challengers bedeviled by 11th-hour withdrawals. A couple were due to Saturday injuries but rumours were percolating early that one no-show was due to a player forgetting a Mother’s Day commitment. This went down a lot worse with the members than any yard glass would.

It left Toko exposed.

Coach Peter Morton, who some years ago broke his neck playing for Toko in a Saturday club match, worries that his reshuffled side didn’t put on much of a show.

I didn’t have the heart to tell him there and then that, in reality, the match was probably the least interesting part of the exercise.

Over the past couple of years I have spent a lot of time and words pondering whether rugby’s influence and essence was waning.

One line of John McBride’s was rattling around in my head: “We need to keep the Dean Cup going. Hell, rugby is a dying sport here.”

As I took years off the life of my car while driving it through the narrow chasm of the Tangarakau Gorge it occurred to me that I, and maybe even McBride, who remains umbilically attached to the national sport, might have been looking at the problem in reverse.

If Taranaki’s rapidly depopulating east is a true gauge, perhaps it is not rugby losing its grip on the country, but the rural country struggling to keep its grip on rugby.

If that’s the case, as long as the Dean Cup glitters from a plastic chair on the sideline, this community will continue to ensure it does not go gently into the good night, but will rage, rage against the dying of the light.