Words: Neil Reid

Design: Paul Slater

From the outside Jimmy Peau seemed to have it all while chasing his boxing dream in the US.

A young family, using a $6 million ranch in the state of New Mexico as his base, getting around in a flash new Chevrolet Camaro sports car, hanging out with Hollywood A-listers and being one of the most popular stars on lucrative cable TV boxing promotions.

But the Kiwi sporting hero — who fought professionally under the name Jimmy Thunder — would sadly become another tragic face of top-level boxing; first living on the streets in Las Vegas, then being deported from America, and last February dying after brain surgery.

Jimmy Thunder walks away after knocking out Bomani Parker in 1995. Photo / Getty Images

Jimmy Thunder walks away after knocking out Bomani Parker in 1995. Photo / Getty Images

As loved ones prepare to remember Peau a year on from his death aged just 54, his family has spoken for the first time about his rise to fame, his sad descent in the US where he was left “with nothing” and then the health battle he waged back in New Zealand.

Youngest brother Chris, aged 47, said one of the saddest things his family had to grapple with was how Peau had isolated himself from his parents and siblings in Australia and New Zealand at a time when he would have needed their support the most.

“Trying to keep in touch with Jimmy was hard,” Chris told the Weekend Herald.

“There was a good period where we couldn’t get hold of him. That is when things started to go down. With Jimmy he didn’t want to rely on us. He didn’t want us to worry, but we were worrying.

“I reckon he had five different managers in the States. [And] they left him with nothing. It [what he went through] is tough. From my perspective growing up and looking up to him and being protective about him in the later years, that stuff hurts. [But] it is the real facts and the real story.”

The Peau brothers had a lengthy phone conversation in 1995 after Jimmy had relocated to the States. At the same time his younger brother was playing professional rugby league in France.

It was the last in-depth conversation they had before the one-time heavyweight world title hopeful returned to New Zealand after being deported in 2014.

Chris Peau, Jimmy’s youngest brother, with some of the memorabilia of the former boxer’s career. Photo / Alex Burton

Chris Peau, Jimmy’s youngest brother, with some of the memorabilia of the former boxer’s career. Photo / Alex Burton

In the resulting 19 years, Peau became a ratings hit for TV boxing promotions, starring on some lucrative fight cards.

But the boxer — who became a national sporting hero after punching his way to a gold medal at the 1986 Edinburgh Commonwealth Games — also suffered numerous body blows, which he was never to recover from.

“In Las Vegas it can be a cruel game,” Chris said of his older brother’s battles.

From being bullied to becoming a punisher

The rich trappings, and dark pitfalls, of the professional scene in Las Vegas are a world away from Jimmy Peau’s introduction to boxing.

While in later life he would prove to be able to handle himself in the ring against some of the world’s best, he was badly bullied as a boy growing up in South Auckland.

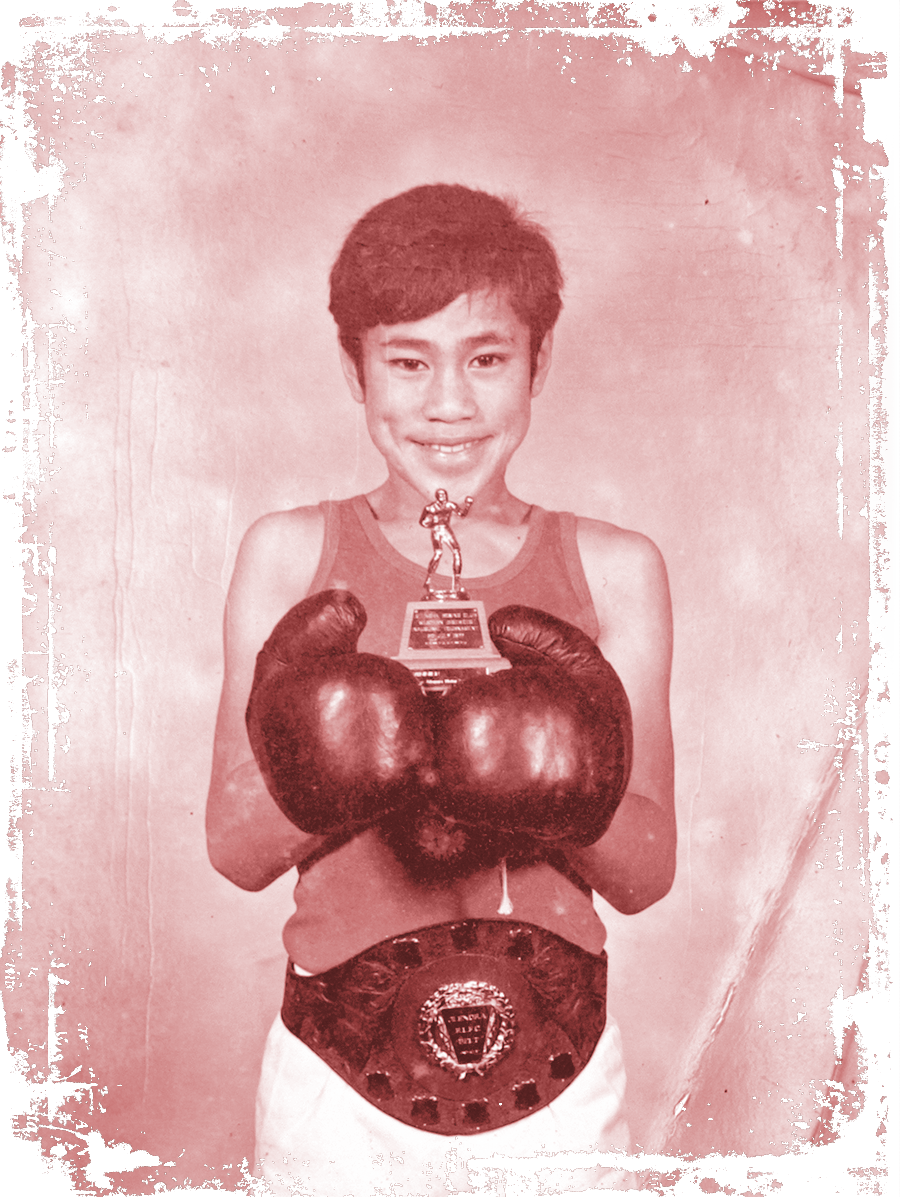

By the age of 6, he walked into a small gym in Māngere

A young Jimmy Peau holding one of the first trophies he won in his boxing career. Photo / Supplied

A young Jimmy Peau holding one of the first trophies he won in his boxing career. Photo / Supplied

Bridge looking for tips on how to protect himself.

“This old fella called Gerry Preston was the coach and said to Jimmy, ‘What do you want?’” Chris said.

“The rest is history. They built a great relationship.”

Three of his brothers, Niu, Johnny and Chris — who like Jimmy were all born in Auckland — would later follow him into training at the gym at a young age.

But Chris revealed they initially weren’t honest about where they were heading after school studies.

“We were all telling our parents we were off to the library as there was a library next door to the gym and we ended up with bleeding noses from the boxing gym. Our parents said, ‘What the hell is going on?’”

A strong work ethic learned from their parents would see the quartet of young boxers make big inroads in the Auckland junior boxing scene.

“We all travelled in Gerry’s little car. I was the first fight, then Johnny, then Niu, and Jimmy was the last fight,” Chris recalled.

“They were the great memories of the amateur days.

“Gerry was a really good coach ... stern. He was very small in stature but very big in heart and voice. He commanded the respect of us.”

Preston religiously closed all the doors and windows to his small gym, with Chris saying the conditions resembled those of a “sauna”.

And in a bid to keep his weight around the 90kg mark, a teenaged Jimmy Peau would also train in the stifling conditions wearing two pairs of tracksuit pants and two hoodies.

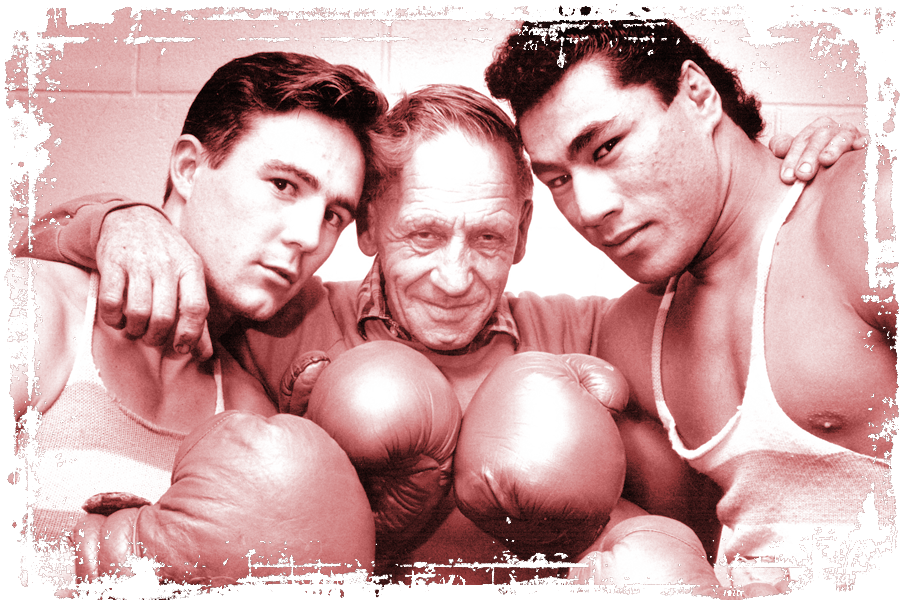

Trainer Gerry Preston flanked by young boxers Bill Handsby, left, and Jimmy Peau in 1987. Photo / New Zealand Herald

Trainer Gerry Preston flanked by young boxers Bill Handsby, left, and Jimmy Peau in 1987. Photo / New Zealand Herald

“We weren’t allowed to take a breather outside,” Chris said. “If you took a breather outside you weren’t allowed back in.”

As well as boxing training, the future Commonwealth Games champion would run up to the top of One Tree Hill at least three times a week.

One of Preston’s more unique training methods was to take Peau out to his Karaka horse stable and get him to outrun his horses early in the morning.

“He released a couple of horses and just told Jimmy to run. You couldn’t see the horses, but you could hear them coming. There was no health and safety around then,” Chris laughed.

Jimmy Peau excelled in a number of other sports at high school; he was in Onehunga High School’s First XV, an accomplished basketball player, and a school track and field record holder.

But boxing was his real calling.

Golden glow in Edinburgh

Peau became an overnight Kiwi sporting sensation after winning a gold medal in the heavyweight division at the 1986 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh.

Prior to heading to the event he was well known in the New Zealand boxing scene, including winning a silver medal at boxing’s 1985 World Cup in Seoul.

But his devastating knockout over Scotland’s Douglas Young in the final saw him become one of the hottest properties in New Zealand sport; becoming a household name and one of the first Pasifika athletes to be warmly adopted by everyday Kiwis.

“At the Commonwealth Games what he brought to our family and the people was huge,” Chris said.

Thirty-four years on, Chris still has vivid memories of the day Peau boxed himself into the hearts of Kiwi sports fans.

The Peau family couldn’t sleep the night before the bout due to their excitement. When the final started their home in Māngere Bridge was packed with relatives and close friends.

“We all gathered around our little TV,” Chris recalled.

“When the Scottish boy went down we all jumped up and a lot of us almost hit our heads on the ceiling.”

The overnight adulation he earned was in stark contrast to his humble upbringing, and he was soon talked about as a future professional boxing star.

He was first sounded out about turning pro by future world heavyweight champion Lennox Lewis’ handlers before the Commonwealth Games. Lewis — who went on to win gold in the super-heavyweight class at Edinburgh — allowed Peau to train at his pre-Games camp in Canada.

“Lennox Lewis really liked him. They [boxing promoters] had plans for Lewis and for Jimmy. But Jimmy didn’t really understand much about sports management.

“Imagine if he did go with Lewis, imagine where he would be.”

While he stayed in the amateur ranks, his growing profile also led to a raft of new jobs, including a role selling cars at a second-hand dealership.

He also worked as a bouncer at the popular Grapes nightclub, a part-time DJ and also as a security guard for Securitas.

Jimmy Peau cuddling his baby boy Loius James Peau in July 1987. Photo / New Zealand Herald

Jimmy Peau cuddling his baby boy Loius James Peau in July 1987. Photo / New Zealand Herald

“He worked with one of my good mates George Mann, the former Kiwi, and he had a competition about who could carry the most money bags into the bank,” Chris said.

“They would roll up their sleeves so they could show their guns [muscles], walk in carrying all these money bags and say hello to the ladies. They were fun times.”

Peau’s profile grew further after winning bronze at the 1987 World Cup in Belgrade.

But despite being rated as a near certainty for a medal at the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games, he never made the team after falling out with New Zealand Boxing Association top-brass.

“I reflect back and go, ‘Shucks, that could have been the turning point,’” Chris said.

“I believe if he went to the Olympics then some good people who saw his talent and cared about him would have given him a good career. But he did it the hard way.”

“They treated him like a greyhound”

“Frustrated” at his Olympic dream being shattered, a 22-year-old Peau packed up and travelled to Australia.

One of his first stops was to Melbourne’s Marco Polo Gym; home to famous Australian trainer Jack Rennie. At the time Rennie was doing some training with a top-ranked Aussie professional heavyweight.

“Jimmy just rocked up . . . and asked, ‘Do you want a spar?’. Jack Rennie, said, ‘Do you know who this guy is? Who are you?’. Jimmy said he just wanted to spar.

“So he jumped in and ‘Boom’, the Aussie went down. Jack said again, ‘Who are you?’.”

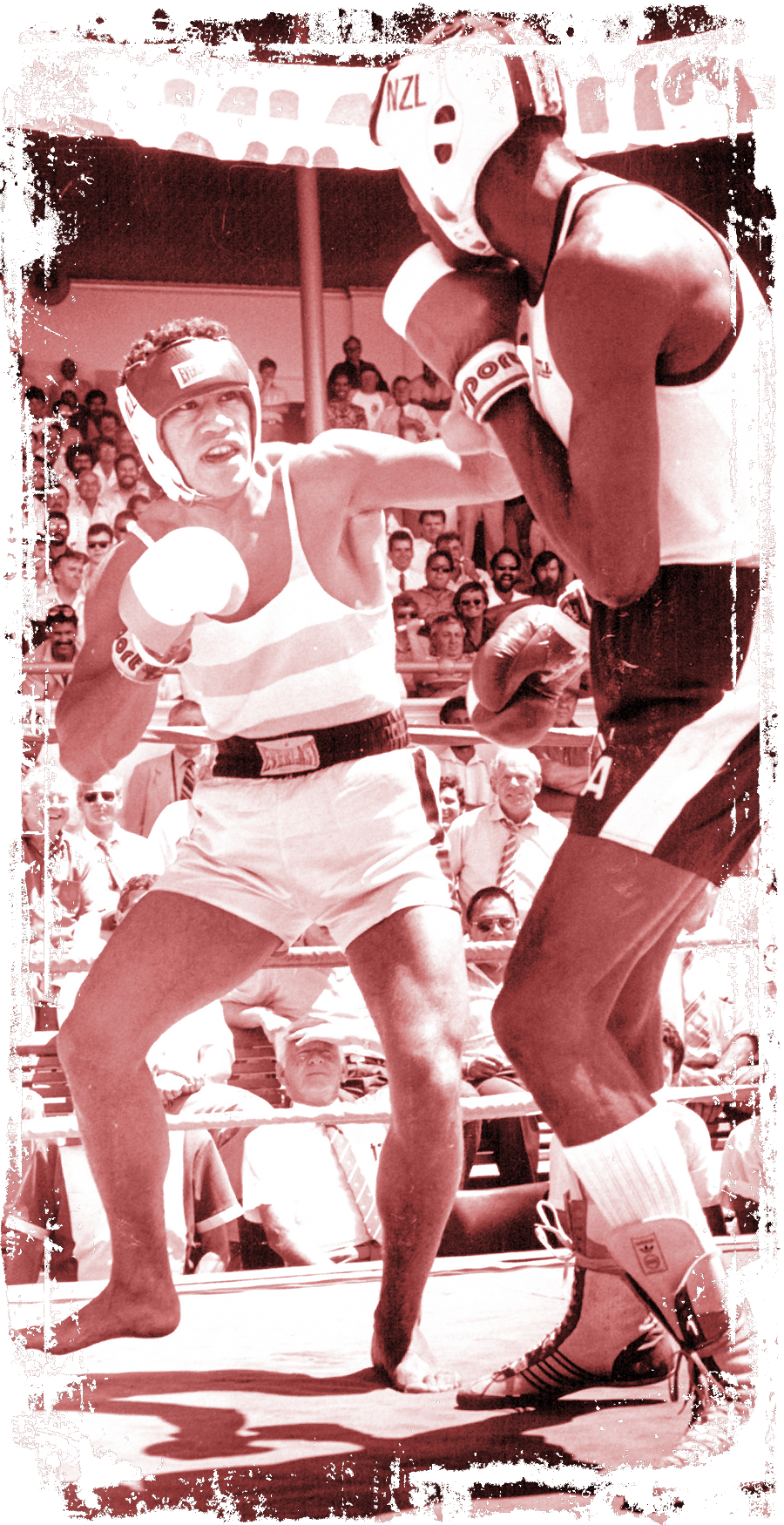

Jimmy Peau unleashes a thundering punch in an international clash against Yugoslavia in June 1987

Jimmy Peau unleashes a thundering punch in an international clash against Yugoslavia in June 1987

That night an electrical storm hammered Melbourne. The wild weather proved to be the inspiration for the new name he would go under as a professional boxer. “Jimmy Thunder”.

He debuted as a pro in an April 1989 with a technical knockout over Fijian Niko Degei in Melbourne. In his fifth pro fight he secured the Orient Pacific Boxing Federation’s heavyweight title.

In 1994, after 23 pro bouts — including two in the UK — Peau decided his future lay in America and relocated to Las Vegas.

“He went off his own bat,” Chris said. “There was nothing signed or any contracts ... he went over just to give it a shot.”

Peau’s cracking fists wasted little time in making their impact in the US.

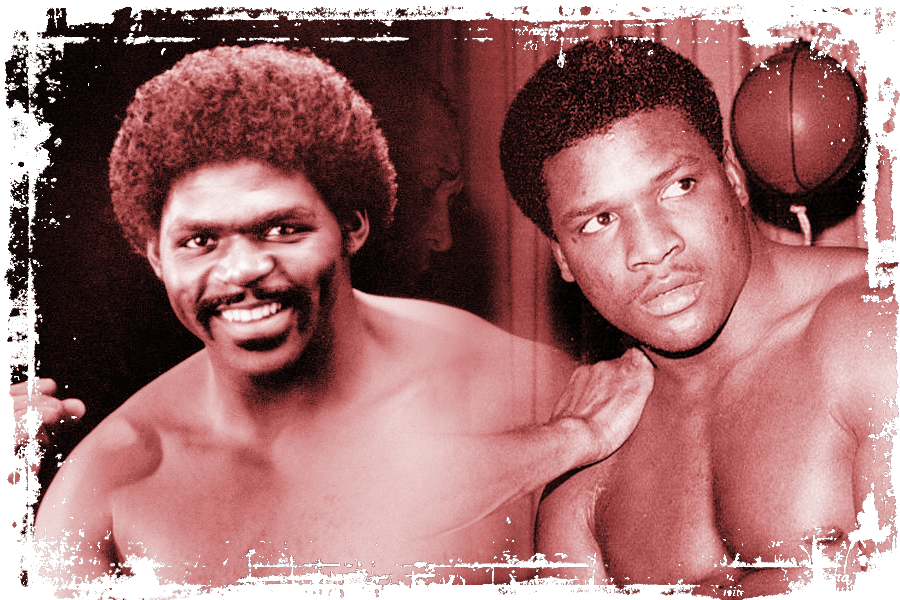

He won his first eight fights in the States, including dispatching former world heavyweight champions Tony Tubbs and Trevor Berbick.

Tony Tubbs and Trevor Berbick. Photos / Getty Images

Tony Tubbs and Trevor Berbick. Photos / Getty Images

And with it came increasing prize money — with Peau estimated to have won several million dollars in purses during his career. For a time he was staying on a $6m ranch in New Mexico, as well as splashing out on a Chevrolet Camaro sports car.

But what was missing was sound management, with Chris saying his brother’s trusting nature saw him fall into the clutches of some promoters who didn’t have his best interests at heart.

“If I look back at his professional record in the States, [at one stage] he had eight fights in 14 months. They treated him like a greyhound,” Chris said.

“It was all about commercial [value]. It was all about cable TV ... they loved him. It was, ‘Get him back in [the ring].’

“He really trusted different guys. He was a yes guy, and if someone said something, he would believe them. That is the downfall ... he went to America and whoever spoke to him convinced him [to do something], he just went with it.”

Peau suffered his first loss in the ring in the States against Franco Wanyama in July 1995. Incredibly, he was back in the ring less than a month later, going on a streak of five unbeaten bouts before losing to future two-time world champion John Ruiz in January 1997.

As well as losing that bout, he had also all but lost contact with his close-knit family back in New Zealand.

But the Peau family’s phones rang hot from well-wishers after his stunning knockout of American Crawford Grimsley less than two seconds into their fight in Flint, Michigan, in March 1997.

Almost 24 years on, it remains a world record for the quickest professional heavyweight boxing knockout.

“We were watching the news, because we didn’t hear from him, and then all of a sudden here is this 1.3-second [knockout],” Chris said.

“My phone was going off. The proudness was there but we just wanted to make sure he was all right.”

A sign of Peau’s management set-up — and his own lack of knowledge over his rights — was when IT giant Hewlett-Packard used imagery of his destruction of Grimsley in a major marketing campaign.

Peau was not paid a cent.

Life on the streets and wanting “revenge on his managers”

Jimmy Peau summed up his family’s fears about the environment he was operating in during a rare media appearance in New Zealand in the late 1990s, describing the scene in Las Vegas as a “rat race” while talking on the SportsCafe show.

His family held various concerns over the handling of his career, with Chris saying they were sparked by constant changes in his team for successive fights.

“When I look back at his fights and look at his corner men, his corner men were all different from time to time,” Chris said.

“He had different managers. You could see how there were a lot of guys hanging on and wanting the fame around him. I look at that and think, ‘You guys didn’t really look after his health.’ That is the one saddest thing.”

In contrast, fellow Kiwi heavyweight boxer David Tua was impressing in his then fledgling professional career under the handling of legendary promoter Lou Duva’s Main Events company.

And his former sparring partner Lennox Lewis had also become a world title belt holder.

David Tua and Lennox Lewis. Photos / Supplied

David Tua and Lennox Lewis. Photos / Supplied

“If Jimmy was in [Lou Duva’s camp], he would at least have a life and be looked after,” Chris said.

He said the care around him also highlighted the lost opportunity in not signing with those looking after Lewis’ move into the pro ranks.

The two former 1986 Commonwealth Games champions did reunite in Las Vegas in late 2000, with Peau being hired as a sparring partner ahead of Lewis’ world title defence against Tua.

“Jimmy sparred eight rounds a day with him, he was under contract and it was some kind of ridiculous money he was paid for each round,” Chris said.

“Lennox respected Jimmy and vice versa. They were good friends. Jimmy said Lennox was good to him.”

Within two years his 49-fight professional career was over; winning 35 (including 28 by knockout) and losing 14 (including being knocked out seven times).

With nothing left financially from his career in the ring, for a time Peau worked security at casinos in Las Vegas, including having to complete 24-hour shifts.

Heavyweight belts won by Jimmy Peau remain in his family’s care. Photo / Alex Burton

Heavyweight belts won by Jimmy Peau remain in his family’s care. Photo / Alex Burton

“[At his height] he got on well with celebrities, especially after that quick knockout [against Grimsley],” Chris said. “He was treated like a rock star.

“Then you end up with nothing and end up working on the floors of casinos.”

Worse was to come when he ended up living on the streets.

“I was always protective of him,” Chris said. “Being homeless, that was all part of his story. You can’t hide that.

“The tough times in Las Vegas took their toll. He had lost trust in people. [Earlier] he did trust people. But that trust ... just went out the door. I don’t think he had any respect for people at the time.”

Earlier his former partner and children had returned to New Zealand.

Chris said his brother stayed in the States as “he wanted revenge on his managers”.

Rock bottom came after he was convicted of assault after an incident at a street party. He was later deported back to New Zealand.

The final fight

Chris Peau was working as a logistics manager in Afghanistan in late 2014 when his wife rang to tell him his brother had returned to New Zealand.

Given the importance of family, the younger brother quit his job and returned home as soon as he could.

“My wife said ... he wanted to get out of that rat race and he caused trouble,” Chris said. “He just wanted to get out of that place and go.

“He came just with the clothes on his back.”

Chris Peau helped care for his brother on his return to Auckland and his later health battle. Photo / Alex Burton

Chris Peau helped care for his brother on his return to Auckland and his later health battle. Photo / Alex Burton

On being reunited Chris could “hear it in his voice” that his brother was unwell.

He put his brother up in a property in Ōtāhuhu and sought medical advice for the clearly ailing sporting legend.

“I pretty much knew what I had to do. I had to take him to a specialist and look after his health,” Chris said.

The first stop was to visit a leading neuropsychologist who handled several athletes suffering from concussion injuries.

MRI scans were carried out and medical experts at the University of Auckland did their own tests.

“We had the best of the best,” Chris said. “It wasn’t about the money, it was about getting him right and getting the best advice.”

Corrective surgery was also completed on a badly broken nose — a legacy of a brutal pounding suffered in the ring — which had impacted on Peau’s breathing.

“I could describe his breathing to being like Darth Vader, especially when my cousin took him to the movies ... this couple was complaining,” Chris said.

“[After the operation] he was like a new man. He was happy, he was punching the air and saying, ‘I can breathe.’”

The silver medal Jimmy Peau won at boxing’s 1985 World Cup in Seoul, South Korea. Photo / Alex Burton

The silver medal Jimmy Peau won at boxing’s 1985 World Cup in Seoul, South Korea. Photo / Alex Burton

The results of an MRI scan later discovered a benign brain tumour about the size of a two cent piece which had impacted on Peau’s vision. Some signs of early-onset dementia were also discovered.

A five-year plan for Peau’s care was agreed upon by a medical team and the former boxer’s family; with the plan including surgery to be carried out in early 2020.

During that time Peau worked for a cousin’s company which erected marquees. Reconnecting with family — including his three adult children — was a priority.

Peau also wanted to “give back” and pass on his knowledge and story to youngsters.

“Throughout that five years ... we celebrated his birthdays because he didn’t have that family around him [when he was in the States],” Chris said.

“If you talk about boxing with him, there was no memory loss with that. He would talk to you for days and tell you the stories for days.

“He had his moments, but for us we just wanted to give him the best and treat him as normal. But we knew in the background there was something wrong.”

Jimmy Peau’s decision to ditch his boots in a clash with England’s Henry Akinwande backfired on him badly. Photo / New Zealand Herald

Jimmy Peau’s decision to ditch his boots in a clash with England’s Henry Akinwande backfired on him badly. Photo / New Zealand Herald

By the time Peau was operated on early last year the tumour had increased to the size of a 50 cent piece.

Still, Chris said the family had been told there was a “95 per cent” chance the surgery would be successful.

But tragically Jimmy Peau didn’t survive.

Due to swelling and subsequent bleeding of the brain he underwent four operations in six days,

“The doctor, because we had an open relationship, it was good because he told me that he was actually going to get worse if he came through ... that it would have been rapid.”

He died in the early hours of February 13 surrounded by loved ones.

Peau was buried at the Manukau Memorial Gardens, South Auckland, in the same row of grave sites as former All Blacks Jonah Lomu and Dylan Mika, and Manu Samoa rugby legend Peter Fatialofa.

A planned unveiling on the first-year anniversary has been delayed due to Covid-19 travel restrictions. It would happen once travel restrictions were eased so his siblings in Australia can attend.

The mention of Peau’s name still brings back fond memories for many of his Commonwealth Games success and brutal punching power that for a time made him a pro heavyweight star.

But for Chris, some of his most poignant memories are those gathered over the five years the family spent reunited in Auckland.

“When he got home it wasn’t about the boxing. It was reconnecting with his family and kids and him meeting his grandkids. That was the most important thing,” Chris said.

“I can honestly say he had the best five years with us. He had family around him and people he could trust. You don’t have that overseas when it is all about fame and money.”

Jimmy Peau: The puncher who wrote poetry

Jimmy Peau admired the legendary Muhammad Ali for his ring craft and his writing ability.

In the lead-up to winning a gold medal at the 1986 Commonwealth Games, Ali’s autobiography The Greatest proved to be a must-read for Peau.

The South Auckland-born boxer’s edition — which is in the safe-keeping of his family — features numerous passages Peau wrote of himself, including the fact he wanted to be a future world champion himself.

And after winning gold, he also penned his own poem about himself; called Young Rising Star, and named after a New Zealand Herald sports award he had won as a youngster.

Young Rising Star — by Jimmy Peau

It all started 20 years past.

One of New Zealand’s greatest boxers

Was born at last.

He had been fighting his way

Right to the top.

Ever since he was a schoolboy

He did not want to stop.

There is something funny

About the way this boy fights.

He plays cat and mouse

And then turns out the lights.

He knocked out the Canadian,

Then he knocked out the Scotsman.

To prove the strength of New Zealand

Was not forgotten.

He floats like a butterfly

And stings like a bee,

And that’s why his opponents

Went out in round three.

This boy was fresh

This boy was new.

The people and boxing fans

Called him Jimmy Pugh.

The name of this true champion

I might as well tell

Is none other than the greatest himself,

Jimmy Peau.