Words: Jared Savage

Visuals: Mike Scott and Alan Gibson

Design: Paul Slater

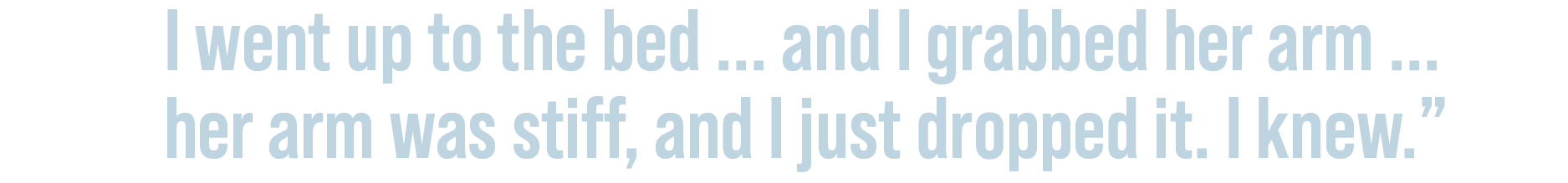

Nancye O’Reilly was bracing herself for a grim winter’s night. Dark clouds were rolling in and although it wasn’t raining just yet, the council-owned house in Avondale, Auckland, where the 27-year-old single mum was living wasn’t built for stormy weather.

It was a turn-of-the-century villa with a single hallway running through the middle, connecting the front and back doors. Draughts of wind would come up straight through cracks in the floorboards, which Nancye tried to cover with mismatched squares of carpet to keep the heat in. Several layers of wallpaper were glued to the scrim lining sagging away from the 12-foot stud walls. The toilet was outside. The lawns were long.

Nancye O’Reilly. Photo / New Zealand Herald Archive

Nancye O’Reilly. Photo / New Zealand Herald Archive

The place was in a dreadful state, but it was all Nancye could afford. She lived there with her daughters Juliet and Alicia, aged 8 and 6, and Isobel, an 18-year-old boarder who helped look after the girls. It was August 15, 1980, a Friday night, and Nancye and Isobel had cooked dinner for their boyfriends, Nigel and Jimmy.

Nigel and Jimmy were staying the night and both couples planned to visit the Victoria Park markets in the morning. When no one was looking, Alicia tipped her meal out of the window. She didn’t like chow mein. As the two girls were getting ready for bed after watching The Dukes of Hazzard in front of the fire, Nancye spotted Alicia walking down the hallway with her dressing gown wrapped suspiciously around her body.

Juliet and Alicia O’Reilly in 1980, aged 8 and 6 years old respectively. Photo / Supplied

Juliet and Alicia O’Reilly in 1980, aged 8 and 6 years old respectively. Photo / Supplied

“Alicia, you’re not taking the cat to bed,” called out Nancye, and there followed a thud as the 6-year-old dropped the cat on the floor. Alicia ran down the hallway, asking her mum to tuck her under her ballerina quilt. Nancye got distracted by the movie on television, so both her girls had fallen asleep by the time she came into their bedroom to say goodnight. Nancye kissed Juliet and Alicia, and went to bed. It was the last time she’d see Alicia alive.

The rain bucketed down on the tin roof overnight, the soothing sound drowning out any other noise in the house.

Nancye got up around 7.30am on Saturday to find Juliet playing with her dolls in front of the heater in the lounge. She thought that was odd; Alicia was always up first. And if she was awake, everyone would be awake. Nancye sighed with relief, she could go back to bed to have a cup of tea and read the newspaper. Her bedroom was across the hallway from the girls’ room, so she could see the lump of Alicia’s body under the blankets.

She went back to reading the paper until another friend of the flat, Jim, came by to pick up some tobacco he’d left behind. As Jim went to leave, Nancye asked him to check on Alicia, so he walked into the girls’ bedroom.

“I saw the look on his face, then he yelled ‘Nigel, can you come here!’ I just jumped out of bed, I knew something wasn’t right,” Nancye says. Nigel's words were followed by a long silence.

Alicia had an obsession with pills and tablets. Nancye raced into the dining room to check a cupboard, high out of the reach of children, where all the medicines were kept. Nothing had been touched.

Nancye went back to the bedroom and pulled back the covers. The Paddington Bear sheets were covered with blood, and she couldn’t understand why. Alicia’s face was purple and swollen. Nancye was repulsed by the ugliness of her beautiful little girl.

She stumbled into the hallway and could hear a woman screaming hysterically. People walking past the Canal Rd house to the nearby Avondale Racecourse stared at her. Nancye realised she was the one crying in anguish. Ambulance staff and police officers appeared from nowhere, to ask questions and take notes. Cameras flashed.

Nancye was taken by police officers to the Auckland Central station, through a back door and into a lift. When the elevator opened, a sign on the door opposite read “O’REILLY HOMICIDE”. She was taken into a neighbouring room and sat down at a table, before a police officer sternly delivered a terrible truth.

“Mrs O’Reilly, we need to tell you your daughter has been brutally murdered and severely sexually assaulted,” Nancye recalls word-for-word nearly 40 years later.

It was a gut punch.

“I just put my arms around my stomach and I just kept rocking and making an awful, awful noise … and then the policeman said: ‘Keep your voice down, your other daughter is in the next room’."

Tomorrow, Sunday, August 16, 2020, marks the 40th anniversary of the day Alicia O’Reilly was found dead in her bed.

Her killer was never found. It’s difficult to imagine a more horrendous crime than the rape and murder of a 6-year-old girl, with her sister sleeping just metres away.

All little girls should be safe in their beds. Nancye O’Reilly was hopeful, of course, that whoever took the life of her daughter would be caught. Weeks went by without an arrest, then months slipped by, which turned into years.

Tragedy would again strike for Nancye, who has experienced more grief and heartache in her lifetime than most people could endure. She’s 67 now and battling cancer.

Long ago, Nancye stopped hoping for justice for Alicia and any thoughts of punitive vengeance gave way to wanting to ask the killer just one question: “Why did you choose my house?”

There may not be an answer. But a veteran detective on the case since day one of the investigation has never given up trying to find out.

His efforts behind the scenes have led Auckland City police to review the evidence on the original file with fresh eyes in 2020, with at least one new line of inquiry to explore.

Allsopp-Smith was a young trainee detective in the Auckland CIB in August 1980 and given the somewhat menial task of securing the crime scene at Canal Rd, Avondale.

A police officer stands outside the crime scene at Canal Rd home in Avondale. Photo / NZ Herald

A police officer stands outside the crime scene at Canal Rd home in Avondale. Photo / NZ Herald

He recalls combing through the long, unkempt grass on his hands and knees looking for clues.

Looking back, Allsopp-Smith says he remembers it was difficult to comprehend the magnitude of what had happened.

He’d worked homicide investigations before, but this was a far cry from a drunken brawl on Queen St which had taken a fatal turn for the worst.

“You find a kid dead in her bed, you don’t automatically think ‘someone’s broken in and raped and killed her overnight’. It’s not a place you can get to without being forced by the evidence,” Allsopp-Smith says.

“And the evidence does force us to. There’s no wriggle room by which you can come to a different conclusion.”

The pathologist who wrote the post-mortem report concluded Alicia was suffocated. He found semen in her body and determined her injuries were caused by sexual assault.

On hearing the disturbing sexual element, Nancye O’Reilly struggled to cope as it brought back memories of her own sexual abuse as a child and the feeling she had failed to protect Alicia from the same suffering.

She also felt a strange sense of relief; the sexual assault was proof she hadn’t killed her daughter.

“I thought ‘Thank God, it wasn’t me’. I was so screwed up mentally at the time, I thought I might have gotten up in the middle of the night and hurt her.”

Fingerprints and a partial palm print were found by police, and cross-checked with 200,000 sets of prints. There were no matches.

If Alicia had been killed today, the semen found would be considered almost iron-clad evidence if the DNA from the sample matched a suspect’s genetic profile.

Police Commissioner Bob Walton, left, and fellow officers outside the window to Alicia O’Reilly’s bedroom. Photo / NZ Herald

Police Commissioner Bob Walton, left, and fellow officers outside the window to Alicia O’Reilly’s bedroom. Photo / NZ Herald

Back in 1980, even the idea of DNA was the stuff of science fiction. There was other forensic evidence, though. Pubic hairs were sent for testing in Australia, which identified the killer’s blood type and as likely being of Pacific Island or Māori descent.

The hair follicles revealed another circumstantial clue. The strands were contaminated with five elements of the periodic table: antimony, cobalt, chromium, barium and iron.

This indicated the killer probably worked in a ceramic or paint industry. In the 1980s, Avondale was a working-class suburb where many residents worked at industrial factories along Rosebank Rd in nearby New Lynn.

More than 600 people were nominated by police, or members of the public, as Alicia’s potential killer.

Without DNA science - or even an eyewitness account for that matter - to point the finger at a specific individual, the murder investigation relied on old-fashioned detective work to whittle down the suspect list.

Many were ruled out because their blood type was different to the suspect’s hair sample. This narrowed the field a little, but the rest had to be interviewed and have their alibis checked out by detectives.

Some of the suspects, who were child sex offenders, had a rock solid alibi. They were in prison at the time.

Others were harder to corroborate. In those days, there were no digital footprints - cellphone GPS, credit card or Eftpos transactions, social media posts and security cameras - to track someone’s movements.

Someone’s alibi often relied solely on the word of a family member, friend or colleague.

“From time to time, we know that people’s recollection can be mistaken,” Allsopp-Smith says.

“That’s why it was so important to get those alibis checked out early, rather than wait weeks or months.”

Nigel and Jimmy, the two men who stayed the night with their girlfriends Nancye and Isobel, were also ruled out. This means the police were looking for a killer who broke into the house, suggesting they had some sort of geographical connection.

Officers went door-to-door in the residential streets around Canal Rd, as well as visiting the commercial businesses, to gather up every detail, no matter how insignificant it might seem.

In particular, the police wanted to speak with anyone working the night shift on the Friday evening, or before the sun came up on the Saturday morning Alicia’s body was discovered.

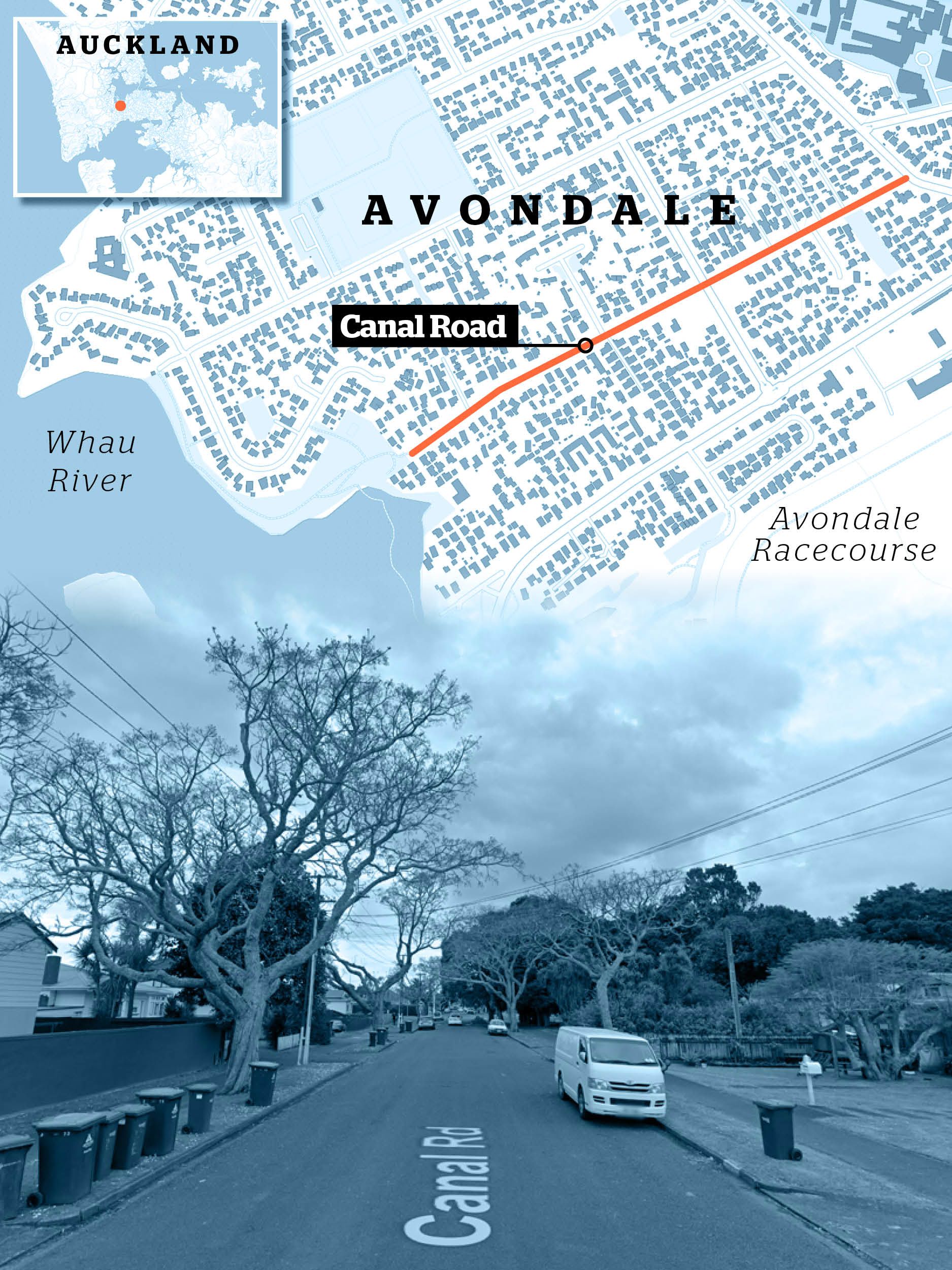

A strongly built Polynesian man, about 1.8m tall, had been seen outside the O’Reilly residence around 6.30am. He was wearing an army-style jacket, dark trousers and boots. An identikit picture was released to the public, but nothing came of it.

Police released identikit images drawn from witness descriptions of a man seen outside the O’Reilly home. Photo / Supplied

Police released identikit images drawn from witness descriptions of a man seen outside the O’Reilly home. Photo / Supplied

The police started to focus their attention on a 23-year-old man who lived nearby. He had suffered permanent brain damage in an accident and had the mental age of an 8-year-boy.

When questioned, the young man denied any involvement but described a vivid dream in which he saw a small boy enter the O’Reilly home, then kill and rape Alicia.

He became the prime suspect but willingly volunteered his fingerprints, as well as hair, blood, nail and semen samples. His blood type was the same, but otherwise no match could be made.

Nancye O’Reilly never really believed this young man was responsible for Alicia’s death, although she can’t put her finger on why.

She had so many unanswered questions that gnawed at her. One thing that puzzled her was why Alicia was brutally killed but Juliet, who was only metres away, was untouched.

“The only thing I can think of was Jules had short hair, and was wearing hand-me-down boys’ pyjamas,” says Nancye, “and that may have saved her life.”

She’s convinced, however, that the 8-year-old Juliet saw what happened to Alicia.

Compared to Alicia, whom everyone regarded as the life of the party, Juliet had always been a very responsible and serious child.

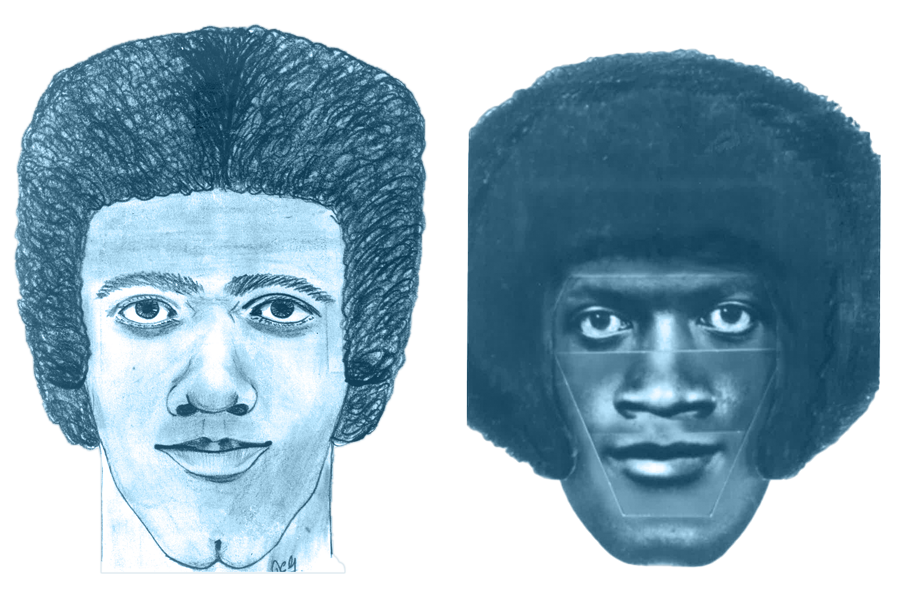

Following her sister’s death, she became even more shy and withdrawn. “I think she saw something. And I think she just shut down,” says Nancye.

The possibility that Juliet had vital information to solve the case was a genuine prospect for the police, who briefly considered hypnotherapy to draw out any repressed memories.

The police poured a huge amount of resources into Operation Sturbridge. Inevitably, as more time passed without progress, the number of staff working on the case dwindled.

The trail ran cold and with it Nancye’s hopes faded as each year passed. Her anguish never waned, she just was just numbed by pain. Then, in November 1987, she was plunged into a new tragedy.

Nancye was left reeling, plunged into a particular grief that few people could understand. Both her girls were gone, in tragic circumstances that no one could predict.

This was different, though, because of the healing power of forgiveness. Where Alicia’s life had been taken in the middle of the night by a stranger, a faceless monster, Juliet had been killed by someone who was little more than a boy himself.

The 20-year-old pleaded guilty to drink-driving causing death and Nancye agreed to meet with him ahead of the sentencing hearing at the Auckland District Court.

“It was a wonderful meeting which ended with him in tears, apologising to me, and I gave him a cuddle. He didn’t wake up that morning thinking 'I’m going to kill Juliet O’Reilly',” says Nancye.

“I copped a lot of flak for forgiving that boy, but forgiving him was one of the most wonderful experiences. A whole weight lifted off my shoulders.”

Nancye learned to live with the pain, and get on with her life. She had a job and a partner and, two years after Juliet’s death, they fell pregnant. However, the joy of creating new life soon dissolved into numbness. Their little girl, Kimberley, died a few hours after being born.

On top of her grief at having to bury a third child, Nancye felt guilt and shame that somehow she was to blame for their deaths.

“By the time the third funeral had come around, I was apologising to everyone for having to come to yet another one of my daughter’s funerals,” says Nancye.

“They saw me as a jinx, they did, 'we might catch it off her'. It’s a very lonely experience.”

Asked how she coped with such recurring tragedy, Nancye says her tough childhood made her resilient. Her father was taken away to a mental institution, and her mother was left to run the farm. When her mother’s anger and frustration boiled over, Nancye copped the brunt of it. She was also sexually abused as a teenager.

She believes the stress and anxiety of her childhood prepared her to cope with Alicia’s murder, and the subsequent deaths of Juliet and Kimberley.

“I had three choices. You could kill yourself, and I had a very religious upbringing so I wasn’t going to do that.

“You could live a half life, and boy, I lived a half life for a long time. Or, you can get on with it. I think that’s it, really.”

As Nancye O’Reilly got on with her life, so did Stu Allsopp-Smith.

His police career progressed through working on countless murders and drug investigations, although the disturbing death of Alicia O’Reilly remained burned into his mind.

Nancye O’Reilly looking through a photo album of her daughters Alicia and Juliet. Photo / Mike Scott

Nancye O’Reilly looking through a photo album of her daughters Alicia and Juliet. Photo / Mike Scott

In the early 2000s, there was a flurry of police interest in cold cases following the DNA breakthrough which in 2002 convicted Jules Mikus of the rape and murder of Teresa Cormack at just 6 years of age 15 years earlier.

Allsopp-Smith, by now a detective inspector, picked up the Operation Sturbridge file again and picked up the phone to call Nancye O’Reilly.

Unlike the Cormack cold case, there would be no DNA success story to solve Alicia O’Reilly’s murder, no science to place her killer before the courts to face justice.

Inexplicably, the swabs containing the killer’s semen were destroyed in the 1980s before DNA testing was available. To this day, Nancye remains angry about the short-sighted decision.

Detective Inspector Stu Allsopp-Smith has kept in touch with Nancye O’Reilly for years. Photo / Mike Scott

Detective Inspector Stu Allsopp-Smith has kept in touch with Nancye O’Reilly for years. Photo / Mike Scott

She didn’t remember Allsopp-Smith combing through the lawn as a young detective all those years ago, but she appreciated the ongoing interest from the senior police officer.

Allsopp-Smith promised to keep her in the loop on any developments, and he did just that over the coming years.

Nancye went on to participate in television shows like Sensing Murder in an attempt to find new clues and solve the case, hoping perhaps the publicity will jog someone’s memory or prick a guilty conscience.

For years, she thought that only holding Alicia’s killer to account could honour her daughter’s memory. But in writing her book, Broken Angels, in 2004, Nancye discovered she no longer felt she needed someone to be convicted of murder. A trial would be traumatic, and wouldn’t bring her closure anyway.

“To be absolutely honest, I don’t care about that anymore. Nothing is going to bring Alicia back, or make up for 40 years of not having her,” Nancye tells the Weekend Herald at her Whakatāne home.

“All of those things that you look forward to ... growing up and leaving home, getting married and having children. A lot of my friends have children that are in their 40s now. It still feels weird for me, I think ‘wow, my kids would be too’. But they’re not.”

Then, last year, came another phone call from Allsopp-Smith. He’d been working away behind the scenes and called to say there was a new lead to follow.

In speaking to the Weekend Herald, Allsopp-Smith is cautious about saying too much in order to protect the integrity of the investigation.

“We do need to hold certain things back, things only the killer would know,” says Allsopp-Smith.

But, given the passage of time, he urged anyone who feels uneasy about an alibi they gave to police in the 1980s to come forward now.

Loyalty and allegiances change, says Allsopp-Smith, in particular when people are in relationships where they might have felt pressure to protect someone with an alibi.

He said no one should let embarrassment or guilt stop them from talking with the police.

“Our only interest is to solve this case.”

If the police were successful, Allsopp-Smith says it would be a career highlight.

“You might be doing something else, and like a wave it washes over you … ‘What about this? What about that?’ It’s never too far from my mind.”

Allsopp-Smith’s persistence has led to the Auckland City police district to review the homicide file with a fresh set of eyes.

Detectives are rifling through boxes of documents and records to scan them into digital files, in order to look at the original evidence through a modern investigative lens.

“Already the team have identified some matters that require further investigation and enquiry,” says acting Detective Inspector Glenn Baldwin.

Glenn Baldwin, acting detective inspector, is in charge of reviewing the cold case with fresh eyes. Photo / Dean Purcell

Glenn Baldwin, acting detective inspector, is in charge of reviewing the cold case with fresh eyes. Photo / Dean Purcell

“What I can confirm is, the small team working on this rape and murder case of a 6-year-old child, are highly motivated and focused.”

There’s been too many disappointments over the years. She’s 67 now and has two adult sons, Jay and Liam, whom she loves dearly.

She got some more bad news when she was diagnosed with a chronic form of leukaemia. The chemotherapy treatment knocks her around.

If the police do find Alicia’s killer 40 years on, Nancye says her need for revenge is now gone.

She’s gone through the anger stage of the grieving process, and says she has forgiven the man who killed her daughter. For her own sake.

She doesn’t want a criminal trial, just a name and face to put to the shapeless phantom which gave her so many sleepless nights. And the chance to ask one question: “Why did you choose my home?”

Nancye tells a story about meeting a burglar who went on to work for an insurance company.

The reformed criminal said he would drive down the street and pick houses to burgle, just off a gut feeling.

“It would be interesting to see if the person who killed Alicia,” says Nancye, “would say it was just a feeling.”

Nancye O’Reilly, who now lives in Whakatāne, with a treasured airbrushed painting of Alicia O’Reilly. Photo / Alan Gibson

Nancye O’Reilly, who now lives in Whakatāne, with a treasured airbrushed painting of Alicia O’Reilly. Photo / Alan Gibson