WAHINE

50 Years of Pain

April 10 marks the 50th anniversary of the Wahine tragedy, which claimed the lives of 53 people after the ferry ran aground in Wellington Harbour.

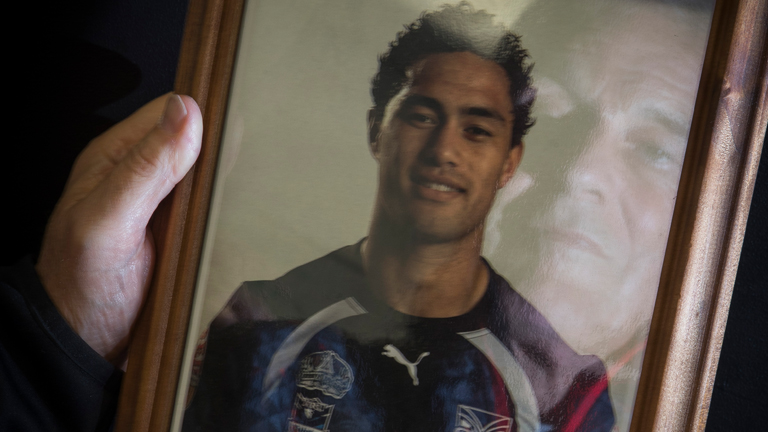

Shirley Hick loved her baby Gordon.

She believes his short life was a good one.

But when he was revived from the brink

of death, after going over the side of the

sinking ferry Wahine wrapped in an oilskin

cloth nearly 50 years ago, she was angry.

Angry that he wasn’t allowed to die.

Angry that she hadn’t been asked.

Shirley, of Shannon, near Levin, had taken three of her children onto the ferry at Lyttelton, near Christchurch, for the journey home. They had delivered her son Peter, 7, to the School for the Deaf at Sumner.

Her 3-year-old daughter, “blonde, beautiful Alma”, dressed in a red coat and a red velvet dress, drowned in the ferry tragedy of April 10, 1968. She was washed across to the far side of the Wellington Harbour entrance from where the Wahine capsized and sank. Son David, 6, was traumatised but survived.

“A male passenger came round … and he took Alma off,” Shirley told the Court of Inquiry soon after the tragedy. “I don’t know what happened [to her] … As far as I know this man took her and put her into a liferaft or a lifeboat.”

She had been put into an adult-sized lifejacket that came down to her knees and was later taken off before she left the ship.

David was screaming and immovable until a steward tied up the youngster’s lifejacket, picked him up and slid him down the steeply angled deck to another steward, who put him into a liferaft.

Shirley had an orange lifejacket put over her head, jumped into the sea, and was picked up after 90 minutes by a lifeboat from another ferry, Aramoana. After a big wave washed people out of the boat, she was hauled back on and held by crew members until rescued by a fishing trawler.

Before she left the ship, she had asked a steward, Brian McMaster, to take 1-year-old Gordon. It was his birthday. The steward initially refused, saying, “No, he might die in my arms,” but he relented, wrapped the baby in what looked like an oilskin and left the ship.

McMaster told the inquiry a lifejacket was placed over the child.

“I floated on my back with the child on my chest … I would say the child died while I had hold of it. He vomited and then foamed at the mouth. Unfortunately the child was then washed out of my grasp by a wave.”

Within minutes McMaster was picked up by 4.3m-long boat, and the seemingly dead child was already on it.

Three days later, under the heading “Baby brought back to life”, the Herald reported that Gordon had been “dead” – meaning his heart had stopped - when he was plucked from the surf at Seatoun, the suburban beach close to where the ferry sank.

A doctor on the beach found Gordon was still alive and rushed him to Wellington Hospital in an ambulance while giving CPR.

“They didn’t really get his heart going until he arrived at the hospital, 20 minutes after coming to shore,” said the hospital’s medical superintendent, Caleb Tucker. “It could be that his very low temperature prevented brain damage.”

Unfortunately this was incorrect: Gordon had suffered severe, permanent brain damage.

“I hit the roof,” 78-year-old Shirley told the Herald in the lead-up to next week’s 50th anniversary of the disaster. “When somebody has been dead for more than a minute, they lose control of pretty well everything in their body. To make Gordie breathe and come back to life … my exact words were, ‘What the f*** have you done there.’ I said, ‘That is my baby. You should have asked permission.’ And their reply was, ‘Oh, we had to save a life.’

“They got him working a bit, and it was a long while, but I brought him home and looked after him as a disabled child.”

Gordon couldn’t talk or walk and he couldn’t feed himself. “All he could do was roll around the floor.”

But Shirley says Gordon had a good life. “I made sure he did. I just loved him and so did the other kids. He was very happy. To me it was a wonderful thing to think that I had kept him alive for all those years.”

Gordon, however, continued to have breathing problems and other health troubles. He died in October 1990, making him the disaster’s 53rd fatality.

Fifty-one people had died at the time of the tragedy, nearly all from drowning although 26 had also suffered head injuries. An elderly woman died several weeks later from her injuries.

WHEN Shirley and her children had walked onto the inter-island ferry Wahine for the overnight trip to Wellington, she was told to expect a rough trip, but she had no inkling of the tempest that would spiral down the North Island overnight to engulf the ship and all on board.

Ex-tropical cyclone Giselle, among the worst storms ever to have hit the country, whipped up the strongest wind measured in New Zealand, gusting to 269km/h at a recording station near the exposed, hilly west coast of Wellington.

Many homes lost their roofs, windows were smashed and several houses were blown down by the wind. Torrential rain caused flooding in many parts of the North and South islands and thousands of farm animals drowned.

As well as the Wahine casualties, the storm killed three people in Wellington – including a girl in bed who was hit by flying roofing iron that smashed through a window – plus a farmer in Kaitaia and a Christchurch man who was hit by a falling tree.

The sinking of the Wahine isn’t New Zealand’s deadliest transport accident – the Air New Zealand plane crash on Mt Erebus in Antarctica had the highest death toll, with the loss of 257 lives in 1979. Nor was it our worst shipwreck – that was in 1863 when 189 died after the Orpheus foundered on the Manukau bar.

But the Wahine storm is branded into many New Zealanders of the time through the black-and-white images of survivors, rescuers and the capsizing ship broadcast on the country’s infant television service; and through people’s memories of their Wahine moment – what happened to them on the day, be it a fence blown down, a road closed or a day off school.

The ferry had received the MetService forecast the night before the disaster, warning of a “severe tropical depression” that was expected to cause rain and poor visibility in Cook Strait and inflict average wind speeds of up to 117km/h and gusts of up to 176km/h.

The vehicle and passenger ferries Wahine and Maori worked the Wellington-to-Lyttelton route as the Union Steamship Company’s Steamer Express service. Wahine had started on the service just over 18 months before the disaster.

WITH 734 passengers and crew, Wahine left Lyttelton at 8.43pm on her final voyage and was due in Wellington the next day. In the run up the Canterbury and Kaikoura coast and across Cook Strait, conditions deteriorated. As the ferry entered the funnel of the Wellington Harbour entrance it was hit by Giselle’s high, strengthening winds and towering waves that were later in the morning estimated to be up to 12m high.

The ferry’s master, Captain Gordon Robertson, 57 at the time, himself the survivor of a shipwreck off the South Otago coast in 1929 when he was an 18-year-old seaman, told the inquiry the weather that sank Wahine was the worst he had experienced in 40 years at sea.

He had never been in such strong winds at the same time as having zero visibility and restricted room to manoeuvre a ship.

At about 5.45am Robertson arrived on the bridge to take control from the senior overnight officer, having earlier been given a 5am report from the Beacon Hill Signal Station overlooking the Wellington Harbour entrance. The wind there was blowing at up to 93km/h. It was about the same in Cook Strait, where there was a considerable swell and it was raining. Sight of the harbour lights and readings from Wahine’s radar showed the ship was on course.

“Do we understand it that you were not worried about the weather?” asked Richard Savage, the lawyer for the Minister of Marine at the inquiry.

“That’s right,” said Robertson.

As the ship passed Pencarrow Head at 6.10am, which Robertson considered the last point for actively choosing to turn tail and head for the relative safety of the open sea, he saw no reason to do this.

The plan had been set. Union Company masters were hired to get their ships into port in all but the most extreme weather and ex-tropical cyclone Giselle did not fit the description. Except that just minutes later arguably it did, at least on Robertson’s account. But it was too late: Wahine was in the harbour entrance and struggling for survival.

After that, accounts from the bridge diverge on key points. But they do agree that at just before 6.10am the ship, engines on half-ahead, veered off course to the left - what mariners call a broach. Robertson said it was by up to 30 degrees and left the ship pointing at Barrett Reef, the rocky outcrop to the left of the harbour-entrance route. The radar navigation system failed, the wind speed doubled to about 185km/h, according to estimates on the ship, and visibility through the rain, cloud and sea-spray dropped to zero.

Robertson ordered the rudders hard to the right. This had no effect. He ordered the engines to full ahead. Still no effect. In big seas, the two rudders and two propellers could often rise out of the water. The ship had turned left side on to the wind. Wahine was in trouble.

Next he planned to use the engines – left full ahead, right full reverse - to help screw the ship back on course to the right.

But then a huge wave violently rolled the ship over to the right – by as much as 45 degrees according to a later analysis commissioned by Robertson’s godson Murray Robinson.

Captain Robertson was thrown 22.5m through the air from the left end of the bridge to the right. He hit the radar set on the way. Others on the bridge and elsewhere on the ship were tossed about too, apart from the helmsman Ken McLeod, who had hold of the wheel.

The 148m-long ship was now drifting at the mercy of the south-south-west storm pushing it up the 1.2km-wide harbour entrance which has steel-piercing rocks on either side.

Confusingly, McLeod later stated that the initial attempts to turn to the right were effective, so much so that the ship had veered towards the right-hand/Pencarrow side of the harbour entrance. He based this assertion partly on the ship’s compass readings. A policeman-passenger’s evidence of wind and waves over the ship from right to left tended to support this.

The discrepancy left an official vacuum in the inquiry’s findings on what happened in the vital half hour after the attempt to correct the veer to the left.

Robertson said his plan now was to continue the ship’s own turn to the left to get back out to sea. But without a radar fix and without visibility, he was completely disoriented – navigating on “instinct and feeling”, as he told the inquiry.

He ordered numerous changes in the direction and speed of the engines as he tried to wrestle the ship around to the south.

He nearly made it, according to retired Cook Strait ferry master Captain John Brown, who studied the inquiry evidence and the time-stamped print-outs of the engine telegraphs, the machines that transmitted engine instructions from the bridge to the engineers below.

Brown reckons that after the swing towards Barrett Reef, Robertson reversed the ship while the wind and sea pushed it up the harbour for 16 minutes. He swung it to the left and was on his way forward to success. But then a new shock: the murk lifted briefly and a light-buoy was spotted roughly ahead – the light was several hundred metres south of the reef’s southern end.

“There's stacks of water there,” Brown told the Herald in the lead-up to the anniversary. “He would have gone out and sunk the buoy but he would have saved the ship. But, instinctively, you see a buoy up ahead … the last thing a mariner would want to do is sink it.”

Robertson had both engines put into full reverse for about five minutes. The ship resumed its northward drift with the wind and sea and at 6.41am the unthinkable happened: Wahine was thrown onto Barrett Reef. The ship’s 3.7m-diameter, five-tonne right propeller and part of its engine tail shaft snapped off like a twig. Water rushed in and the left engine soon died, leaving the ship without propulsion.

A mayday message was sent ashore:

“SOS, going ashore near the heads.”

AS Wahine began to drag along the eastern side of the reef, suffering more damage to the hull, her two anchors were dropped – something that critics later argued should have been done at the start of the crisis.

The ship began to pendulum back and forth on the anchors, nearly running aground again at Point Dorset on the mainland north of Barrett Reef. The storm intensified as the ferry continued its slow drift up the harbour.

Reassuring messages were broadcast to passengers, who had been called up to a muster station and were told to put on lifejackets.

Water from flooded compartments in the bottom of the rolling ship slopped up onto the main vehicle deck through ventilation shafts and over the sills of closed doors. It couldn’t drain out through external valves because the ship was now sitting several metres lower in the water than usual. Gradually the water built up despite efforts to control it, threatening the ship’s stability.

About 11.30am, the tug Tapuhi ventured near enough to get a tow line attached – an 11.4cm-diameter steel cable that had to be hauled onto the ferry manually because electricity to the winches had failed. The line snapped.

Near Steeple Rock and just 400m from the beach at Seatoun, Wahine swung around to be left-side on to the wind as the storm began to ease and the water earlier pushed into the harbour by the gale started flowing out again.

The unstable ferry, which had already tipped slightly to the right, fell into a steep list and at 1.25pm Robertson ordered abandonment.

Only the four lifeboats on the lower, right-hand side of the ship could be used. People had to negotiate the steeply sloping deck to get into the boats or jump off the ship.

One lifeboat was swamped, and then capsized in the surf on the eastern side of the harbour. One made it safely to a beach on that side and two to Seatoun.

The ship also carried more than 30 inflatable liferafts. They were “one of the calamities of the Wahine”, says Robinson, an author who has researched and written extensively on the disaster.

“They were described as flying spectacularly like kites in the air,” he told the Herald. “Only about a third of them, correctly inflated, right side up, were able to be used. There are horrendous stories of survivors standing on these partially inflated liferafts, on the bottom of them because the thing is upside down, in water up to their chest, huddling together.”

CAPTAIN Brown, 81, recalls the day of the disaster clearly.

A Wellington Harbour Board pilot at the time, he set off in the launch Tiakina with a crew of three as soon as he heard the ferry was on the rocks.

He spotted Wahine’s trace on Tiakina’s radar at around 8.30am, but the “massive seas” rolling up the harbour south of Steeple Rock made it too dangerous to venture closer.

He had picked up deputy harbour master Captain Bill Galloway at Seatoun. When the weather eased a little around midday, Brown manoeuvred Tiakina alongside the still-heaving Wahine to allow Galloway to make the dangerous leap onto a ladder and climb aboard.

After people began jumping off Wahine, Tiakina “fished up a few” – about eight. But it was hard to get them onto the high-sided launch. The launch also towed one lifeboat and two liferafts towards Seatoun, after which a rope tangled around one of Tiakina’s two propellers which “half-immobilised us”.

The tug Tapuhi picked up 174 survivors and many other boats helped out in the atrocious conditions too.

Captain John Brown / Photo: Mark Mitchell

SOME blame the Wahine disaster on a sudden, catastrophic worsening of the weather as the low-pressure system Giselle collided with a southwesterly cold front just as the ferry nosed into the harbour entrance. MetService forecaster Erick Brenstrum has a different view.

He says that overnight the low did speed up slightly – but still within the forecast’s stated levels of uncertainty – and deepened a little. At about the time the disaster struck, its direction changed to a more southerly track, bringing it closer to Wellington.

“Some people have focussed on the cold front over the South Island. However, I believe this process [Giselle ingesting colder air the further south it came] was already happening before that cold front reached the low.

“To fuss too much about the timing of the cold front reaching the system just as the low reached Wellington is to buy into the idea that there was a special moment, just as Wahine entered the harbour, when the wind increased greatly. This is not true, as shown by the wind at the airport, which only increased gradually and did not reach maximum until 9am or soon after.”

Wahine was already in trouble by the time the wind speed exceeded the forecast, says Brenstrum

Brown – like the Court of Inquiry – believes the wind estimates made on the ship were excessive. He thinks the ship would have lost speed in the broach, making the wind seem stronger than it had been.

The court criticised the ship’s most senior officers, its owner and the Harbour Board for mistakes that led to delays in rescue boats getting to Wahine, but it found the formal charges laid against them were not proved.

Three of the specialist advisers to the inquiry’s head added their own, dissenting opinion, including that the ship’s “flume” tank, a stability device, should have been used to dampen the rolling and improve steering.

Given the conditions at 5am, the ship’s officers should have anticipated they would be worse at the shallower harbour entrance. Had Robertson been told of the deteriorating conditions at 5am, and that they would probably be worse by the time they got to the harbour entrance, he could have made a “considered decision” about whether to enter the harbour or remain at sea.

“We consider that having made the decision to enter the harbour it should have been at full speed, so as to retain the maximum manoeuvrability in the run to the safer water beyond Barrett Reef.”

THE abandonment of Wahine was a tale of two coasts.

An NZPA report in the Herald said that on the “Seatoun side of the harbour, lifeboats carried passengers, often in dry suits, 400 yards to safety. On the other side of the harbour was the horror. Corpses lay strewn along the jagged rocks of Palliser Rd, near Eastbourne.”

The waves crashing onto the rocks were up to 6m high. In all, 223 survivors landed on the eastern shore and lived. Forty-seven people’s bodies were retrieved there, of whom 12 had come ashore alive. Two of Wahine’s lifeboats, the two from Aramoana, and many liferafts ended up on the eastern side.

Eastern rescue efforts were hampered by the remoteness and landslips blocking the coastal road until earthmoving machines could be brought in.

RICK Ellis believes it was pure luck that drove his liferaft into a bay on the Pencarrow coast, rather than tossing it onto the treacherous rocks.

“You would like to think that if anything happened like that again that they would have surf lifesaving teams or something out there. Because that’s where people were dying,” says the 72-year-old retired teacher from Hawke’s Bay.

“There were two or three instances where people seemed like seaweed. They were still alive but they didn’t quite have the strength to drag themselves up out of the water. A wave would wash them in and the tide would drag them back out.”

He and his mates hauled others out of the water. He kept thinking “help must be coming soon”. But it didn’t, so Ellis and several others persevered, trying to salvage as many lives as they could.

“Thinking back it was probably the first time in my life I had seen a dead person.”

Aged 23, he had been on the ship as a member of the University of Otago cricket team, who were travelling to the New Zealand Universities Easter Tournament. He recalled being woken in his cabin at about 6am by a steward bearing a steaming cup of tea and news of “unbelievably big seas”. He bypassed the cuppa and raced to the top deck for a look.

“The ship was sort of wallowing. It was going to and fro and at that stage I saw some rocks, which turned out to be Barrett Reef, only about 40 or 50 metres away.

“Unbeknown to me, there were rocks that were even closer and soon the ship would actually go up onto the rocks that I hadn’t seen.”

After the grounding, the team joined the throng of passengers in one of the ship’s lounges for several hours. Then the mood suddenly changed. A violent movement as the ship listed knocked people from their feet and tipped chairs on their sides.

There was worse to come as people had to zoom down the steep, slippery deck on their backsides, some suffering broken limbs.

“That’s how quite a few of the injuries happened, people sliding from the high side to the low side on the wet deck were smashing into the side rails of the boat,” says Ray Hutchison, one of the cricketers.

The young men had to choose between the long lifeboat queue and the rubber liferafts. Ellis and Leach chose a raft.

“The waves were absolutely enormous,” says Ellis. “There were a lot of people in the water and they were frantically blowing the whistles on their lifejackets trying to get our attention.”

FOR three of the sportsmen, the disaster marked a turning point in their cricketing careers.

Murray Parker recalled a conversation with Murray Webb, who became a caricature artist. “One of us said to the other, when we were getting out, ‘If we survive this, let’s play for New Zealand’.”

Both achieved that dream. But for Alan McDougall, the sinking of the ship, and with it his cricket gear, was the end of his serious cricketing days.

Parker, 19 at the time, ended up in a lifeboat with Hutchison and Keith Lees. They later pulled Chas Recordon aboard.

“We spent three hours or so making our way to Seatoun, which was into the teeth of the gale really. We rowed the boat in; the people down the bottom of the lifeboat just wound a pipe that was attached to the propeller. It wasn’t exactly breaking any speed limits.”

The Seatoun waves were “bloody high”, says Parker. “We threw a rope out and people on the beach sort of grabbed it and ran up the beach, keeping us front on. If we had broadsided we would have tipped; we were really lucky.”

For Gary Murphy, too, the doomed cricket trip was a turning point.

Standing on the ship and watching people suffer injuries as they jumped into the lifeboats and landed on others, he decided to leap into the water.

And then he prayed.

“At the time I was a church-goer, but I wasn’t a Christian,” he says. “I did pray that day though, I remember praying.”

In those hours a spiritual switch flicked on, when he believed God oversaw his being scooped out of the water and into a lifeboat. Some years later, Murphy became a Christian and then a minister.

Recordon, a Queenstown dentist, looks back on the ordeal and its aftermath and muses over how differently it would be dealt with today.

“Nowadays, every single person would be under counsellor guidance and who knows what else.”

At a reunion with his cricket team he had learnt that several of his teammates still had nightmares about the incident. But personally, he didn’t feel the incident had lasting effects. He felt the lack of coddling likely did him, and several others, a world of good.

“People feel that if they don’t need to go to the counsellor well, then, they’re not grieving enough. And that’s a very negative effect - it can only fuel the wrong feelings. It can make people feel like they need to feel bad about things when there’s a disaster.”

FOR Shirley Hick, her Wahine feelings are never far away.

Alma and Gordon are buried in the Shannon Cemetery, a kilometre from her home. She has attended Wahine remembrance services in the past, but is now mostly housebound. She does her remembering at home.

“I think about it every day. I live it every day. I’ve got things here I had when Alma was alive, the toys, the beautiful photos of Alma and Gordie.

“I’m a tattooed, tough little girl – I’ve got tattoos all over me, I’ve got the Wahine tattooed on my back, across the centre of my back.”

Photos: Mike Scott, Mark Mitchell, NZ Herald Archive, Morrie Hill, Stuff

Video: Mike Scott

Design: Jennifer Adams

Graphics: Phil Welch