The Misery of Marie

A troubled life, brutal love and "absolutely preventable" death

Someone should have seen this coming: that the man Marie Harlick was once in love with would stomp and beat her so brutally that she choked on her own blood, her body left limp in a bathtub with the tap running as life drained out of her.

Her 19-month-old daughter Vivienne, strapped into a stroller nearby, would be left traumatised from witnessing her mother’s murder at the hands of a jealous and controlling Mongrel Mob member, Robert Roupere Hohua.

Next door to the Opotiki house where she died, two teenage friends heard the yelling and beating, called 111 and wanted to intervene. But the mother of one of the boys stopped them from going next door, fearing they too would be hurt.

By the time the police arrived – 26 minutes later – Hohua had dragged Marie’s limp body, stripped off her wet clothes and laid her on a mattress, half-covered in a blanket.

Her face had been washed and her infant daughter was lying next to her. On the screen on Marie’s mobile phone was her sister Vicki’s number, a call she never managed to make.

Marie Harlick was a 35-year-old mother-of-seven – two who died in tragic circumstances – when she died, the victim of unspeakable domestic violence.

“Was I the last person she tried to call? I don’t know,” says Vicki Harlick, through tears.

“I don’t think I did enough. I pretended everything was okay, when it wasn’t.”

Vicki is grief-stricken and guilty about not doing more to help Marie escape a life of escalating violence.

But the failure is more widespread – a dysfunctional family, various agencies that didn’t see the warning signs despite multiple incidents and, in the end, Hohua himself.

A Herald investigation found that many people had many chances to intervene in the sad life of Marie Harlick.

- Police recorded 33 family violence incidents involving Marie.

- Her baby daughter Vivienne was red-flagged with Child Youth & Family.

- Corrections changed Marie’s home detention address. Hohua was not allowed to live with her, as part of her sentence conditions, but did.

- Hohua was twice freed on bail for assaulting Marie, despite strong police opposition, before killing her.

“The death of Marie was absolutely preventable,” says Jane Drumm, executive director of domestic abuse charity Shine.

“And there are so many other women suffering like her. It’s terrible on a human level. And it’s terrible because it’s costing this country billions of dollars.”

Marie Rose Harlick was born on April 13, 1981, in Whangarei. She grew up in Tikipunga, near Whangarei Falls, where everyone called her Mush but no one can remember why.

She was no stranger to crime. The mischief started with stealing fruit from orchards and lollies from the local dairy. Later, she and Vicki stole cigarettes.

Marie, of Ngati Porou and Ngapuhi descent, had a distant relationship with her mother and was, she told her probation officer, “handed around the family”.

Her teenage years were marred by sexual abuse, Marie also disclosed.

Changing homes meant constantly changing schools, so by the age of 12 Marie had stopped going. By 13 she was drinking alcohol, which became a lifelong comfort and companion.

Against a backdrop of rejection and family dysfunction, both sisters wanted to find their absent biological father but, says Vicki, “he didn’t want anything to do with us”.

That rejection was a bitter blow to Marie. “It sort of broke Marie’s heart,” Vicki says. “To this day I think that was the missing piece in her life.”

In their teens, the sisters moved to Taupo Bay, near Mangonui in the Far North, where their stepfather grew up.

There, Marie met Eddie Tatai and, at 17, fell pregnant. The couple would go on to have five more children but their years together were a time of turmoil and trouble.

They moved to a state house in Kelston, West Auckland, but by 2009 Marie was evicted for cheating Housing New Zealand after declaring she lived alone to get cheaper rent.

Neighbours complained of frequent drinking and partying.

Marie and Eddie moved to New Plymouth and, in 2010, celebrated the birth of their sixth child, a daughter they named Frances. Three weeks later Frances was dead.

On the night of June 18, the couple invited friends over for drinks and put the children, including the baby, to sleep on a single mattress in the lounge. Late that night Marie joined her children in a “fairly intoxicated” state, Coroner Carla na Nagara found.

When Marie woke up, Frances was not breathing and cold. The coroner found the baby died of accidental asphyxiation. Although Frances had a cot she was put to sleep in an unsafe place.

“This case serves as another tragic reminder of the risks when safe sleeping advice for babies is not followed. I extend my heartfelt sympathy to Frances’ family for their loss.”

It was not the last time Marie would grieve for a child. Nor would it be the last time alcohol would play a part in her troubles.

A few days after Christmas in 2012, Marie kicked a female taxi driver for refusing to give her and the children a ride.

The reason? Marie was drinking and wanted to take an open bottle of alcohol in the cab.

"If that's the way you behave when you tip liquor down your throat it's best to give it away,” said Judge Allan Roberts in sentencing her to 100 hours of community work.

Two months later, the same judge jailed Eddie for 21 months for injuring with intent and assault with a weapon.

The weapon? A loose pantry door that he threw on Marie then jumped onto.

There was more misery when Marie’s handsome boy Piripi, raised by his paternal grandmother in Taupo Bay, was found dead.

Newspaper headlines reported an unnamed 10-year-old boy committed suicide as part of a cluster in Northland.

His death was later ruled accidental by coroner Brandt Shortland.

Piripi’s unexpected death on top of the loss of baby Frances plunged Marie into depression.

Evicted yet again from a state home in 2013 – she was behind in her rent –Marie left Eddie and New Plymouth behind, moving to Whakatane to be with her sister.

Vicki Harlick remembers the morning Marie arrived at her doorstep, beer in hand.

Vicki had been living in the eastern Bay of Plenty for 15 years and wanted to help Marie have a better life, settle down.

“There were a lot of things swept under the carpet when we were growing up," Vicki says. “I just wanted to do anything to help her.”

The sisters gathered Marie’s four daughters, who were scattered across the North Island, and settled them into schools in Whakatane. It was a good start.

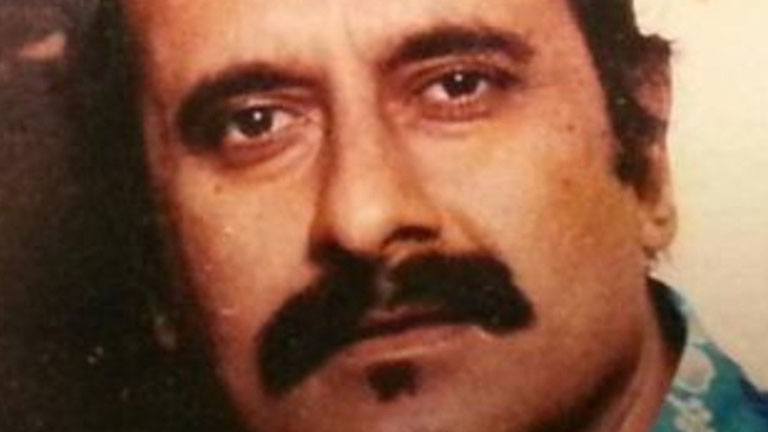

But Marie met Rob Hohua, a Mongrel Mob member. They moved into a Housing New Zealand home together.

Vivienne was born in March 2015. Marie was already pregnant when she met Hohua, Vicki says, but his name is on the birth certificate.

“Love you my princess," Hohua posted on Facebook with a photograph of the baby.

But that show of tenderness was an isolated one. Once again, Marie’s life was overshadowed by violence and alcohol. The couple became “well known to police”, a euphemism for troublemakers.

The police were constantly being called to their home to stop Hohua bashing Marie.

Vicki: “Every time he got arrested, he’d ring me up for bail, bail, bail. And like a dumb bitch, I’d do it because my sister was begging me.”

Because Marie refused to give evidence against him, Hohua had only one conviction for violence against her: a common assault in May 2015.

A year later, the couple were evicted from their Housing New Zealand home.

After an anonymous tip, police searched the Churchill St address and found six cannabis plants ready for harvest.

They also discovered more than 1.6kg of dried cannabis head, scales and resealable plastic bags for packaging.

Marie claimed the dope was for personal use but quickly pleaded guilty to possession of a Class C drug for supply.

Vicki suspects her sister was taking the rap for Hohua, a belief shared by the probation officer who interviewed her and noted several police callouts for family violence.

“Ms Harlick claims she is in the process of removing herself from this relationship. The report writer voiced her concerns … and challenged her reasons for taking full responsibility of the charge, however Ms Harlick declined to shift the blame.”

The report noted Marie smoked weed daily because she “cannot sleep without it” and that alcohol had been a “huge problem” since she started drinking as a 13-year-old.

She also disclosed sexual abuse as a child, which led to “many years” as a victim of domestic violence, the probation officer wrote.

“[Marie] says she has always been told what to do and when to do it.”

Even if she was protecting Hohua, she had taken responsibility in the eyes of the court.

Sentencing Marie to eight months’ home detention in August, 2016, Judge Louis Bidois had a warning.

“Make sure you comply with this sentence Ms Harlick. You put one foot out of place and you will end up in jail.”

It was not the last time Judge Bidois would make a decision with consequences for Marie.

Marie moved to Opotiki. Less than five weeks later, she had moved back in with Rob Hohua.

Corrections approved the change in Marie’s home detention address, after the relative she was living with became tired of Hohua turning up.

As part of Marie's sentence conditions, Hohua was not supposed to live with her at the new address on Wellington St, because of the probation officer’s concerns about their violent relationship.

But like so many other times they flouted the rules.

The couple were drinking with friends at their new home when an argument rapidly escalated.

Marie, drunk, hit him in the face. Hohua punched back, then stomped on her face twice as she lay on the ground.

Her daughters, 11 and 12, tried to stop him but were shoved out of the way. They called 111 and when police arrested Hohua, he tried to use baby Vivienne as a shield.

Marie was charged with breaching her home detention conditions. Hohua was charged with assault with intent to injure.

“They rang me to see if I would bail him out,” Vicki Harlick says. “And this time, for the first time, I actually said no. I felt like a dick but I just had this feeling something bad was going to happen.

“Mush begged, begged, begged … when I told her no, I didn’t want him bailed with me, she didn’t text back.”

Assault with intent to injure carries a maximum sentence of three years in prison, so combined with his age and criminal history, Hohua had to convince a judge he should be released on bail.

Specifically, under the Bail Act, he had to satisfy Judge Bidois he would not commit any offence “involving violence against, or danger to the safety” of a person, or a burglary.

Hohua had 73 convictions and 48 sentences of imprisonment, many for burglary or car theft, dating to 1997. Another 17 offences were committed on bail.

In opposing bail, police pointed out Hohua was named in three Police Safety Orders, each forcing him to leave home for several days to protect Marie from further violence.

“The defendant is a Mongrel Mob member and made it clear during his arrest he is ‘not to be messed with’.”

“Unfortunately, the adult victim outright denies any assault and the prosecution is reliant on her daughter. She told police she doesn’t like seeing her mother being beaten up.”

Near the top of Hohua’s long criminal history was a conviction for common assault against Marie the previous year.

However, this wasn’t drawn to Judge Bidois’ attention. In fact, in granting bail, the judge erroneously noted in Hohua’s favour that his previous conviction for violence was in 2005.

“You are obviously not subject to a protection order because there are no breaches,” said Judge Bidois.

“Your history of non-compliance with court orders is poor. Breach of intensive supervision, driving while disqualified but you do not have a history of significant violence that we see.”

And with that, Hohua was released to live with a relative on Windsor St, less than 1km from Marie.

“These are serious charges, Mr Hohua,” said Judge Bidois. “You put one foot wrong you will be in the can.”

But five weeks later, the police were called to Wellington St. Hohua was found hiding in the backyard, in breach of five bail conditions.

Again, police opposed bail. They said officers had been called to stop Hohua hitting Marie four times since the couple moved to Opotiki and noted seven similar callouts during their time in Whakatane.

They noted Marie was on home detention when Hohua came calling and unable to escape lawfully.

But Judge Bidois gave him another chance.

“I am not sure what is going to happen to you, Mr Hohua, but I do know one thing,” he said. “You breach your bail, you touch her, you see her again and you will be going to jail.”

Hohua simply ignored every condition of his bail – not to go within 100m of where Marie lived; not to contact her; not to drink or do drugs; an overnight curfew.

Instead, on the night he killed Marie, Hohua went to her home where they drank and smoked cannabis with four other people. It was a Tuesday night, November 22, 2016.

Worried about his curfew, Hohua went back to Windsor St just before 7pm. He took Vivienne, by then 19 months old.

But worried Marie was being unfaithful, Hohua walked back to Wellington St, pushing the toddler in a stroller.

He knocked on the door. No answer. Fuelled by his belief that Marie was cheating on him, Hohua broke in.

Stalking from room to room, he didn’t find Marie until she walked in the back door.

Intoxicated, she didn’t answer immediately when he asked where she had been.

So he punched her in the face. A second blow knocked her onto the kitchen floor, unconscious.

A neighbour called 111 at 9.58pm. He could hearing fighting, a baby crying and items being thrown around the house.

The teenager was told to call back if the violence escalated.

Prone on the ground, Marie was defenceless. Hohua punched her twice more in the head, then started stomping and kicking her in the stomach.

“Get up off the ground so I can beat you up,” he screamed. “Get up before I kill you.”

Hearing the stomping and the threats, the neighbour called 111 again at 10.06pm.

If the police didn’t get there soon, the teenager said, he’d go himself.

Marie started choking on her own blood. Hohua dragged her to the bathroom and washed the blood from her face.

She was left in the bath, under a running tap, while Hohua went to check on Vivienne, still strapped in the stroller in the lounge.

The 19-month-old was crying.

Marie was still choking on her blood. Hohua came back to take off her wet clothes, then laid her on a mattress in Vivienne’s room.

The lower half of her body was covered with a blanket; Vivienne was placed beside her dead mother, hidden under the blanket.

At 10.24pm, the police arrived.

Hohua fled out the back, stopping only when he was Tasered. No one was inside the house, he told police.

A blood trail in the dining room led the officers to Marie, but she didn’t have a pulse. They tried CPR but 10 minutes later, Marie was pronounced dead.

The post-mortem examination report of her injuries is upsetting.

Heavy bruising, swelling and cuts to both sides of her face. Bruises on the back of her arms where she tried to protect herself.

Both sides of her jaw broken, completely separated from her skull. More than 2 litres of blood pooled in her stomach and abdominal cavity.

The report said the final cause of death was “multiple blunt-force trauma”.

When the police called Vicki around midnight she assumed she was the one in trouble. But no, the call was about her sister. The officer asked if Vicki was sitting down and had someone with her.

“He said, ‘We’ve got some bad news ... your sister has been murdered’,” says Vicki through tears.

“I was screaming and yelling. I don’t remember what they were saying, my mind was gone. I couldn’t sleep.”

Beneath a deep grief for the loss of her closest sibling lies guilt.

As someone who untangled herself from a violent relationship, with the help of a friend, Vicki can’t help but feel she could have done more for her sister.

But she has questions, too, over what government and social welfare agencies could and should have done.

Why didn’t someone join the dots between a history of abuse and violence, police callouts, Child Youth and Family alerts? Why did Corrections fail to detect Marie was living with Hohua while on home detention? And why did Judge Bidois let Hohua out on bail, twice?

Chief District Court Judge Jan-Marie Doogue declined to comment on the bail decision. Each judge is independent and their rulings speak for themselves.

However, Judge Doogue, who has been leading reform in how the judiciary deals with family violence, agreed to be interviewed about the wider issues at a later date.

Child, Youth and Family (CYF) has been replaced by the Ministry for Vulnerable Children, Oranga Tamariki.

The Ministry confirmed CYF was “working with the mother at the time of her death around keeping her and her child safe” but declined to comment on details of the case, in the best interests of Vivienne.

However, Bay of Plenty manager Tayelva Petley said staff are sharing “critical information” with other agencies as part of the ongoing change at the new ministry.

As for the monitoring of Marie’s sentence of home detention, Corrections said probation officers reported there was “no sign of Hohua at the premises during visits”.

Vicki: “Everybody knew.”

Three weeks after the October assault by Hohua, Marie posted a message on Facebook: “I don’t think I’ll be in love with you ever again. You’re too evil for me and I don’t think I can trust you anymore.”

The day after she was murdered in November, a relative replied: “F*** cuz, you shudve stuck to this. F***, f***, f***.”

Experts say the assumption any victim can simply leave or get help is wrong. They say we need to think differently if we want to change our appalling family violence record.

New Zealand women suffer the worst rates of physical and sexual violence by their partners among developed nations, according to a Cabinet paper for a ministerial working group set up by the previous National government.

On average, 16 women are killed by their partners each year, per capita double the rate in Australia, Canada or the United Kingdom.

Family violence costs New Zealand an estimated $4 billion every year.

That’s the burden on government agencies like health and justice, as well as lost economic productivity.

We spend about $1.4 billion on the problem each year. But analysis of state spending says almost 90 per cent goes on cleaning up the aftermath - not prevention.

The analysis says the investment is “not always effective, not joined up and not targeted at the right points of the system”. It concluded various agencies work in “silos”, responses are often unavailable and poorly measured for effectiveness.

In other words, the response has been fragmented. Multiple agencies each have only part of the picture. So the level of risk can be misjudged; an opportunity to intervene can be missed. And another woman, or child can be killed.

The previous National government oversaw the successful trial of an Integrated Safety Response (ISR) model in Christchurch and Waikato.

ISR referrals are made by police or prisons when an inmate with relevant history is about to be released. Specialists from multiple agencies meet to discuss the risks and make a plan for their reintegration into society.

According to an evaluation released in August, the system is working, and the seriousness and frequency of violence dropped significantly six months after the victim came under an ISR.

But the future of the scheme is uncertain with a new government in power.

Green MP Jan Logie is now in charge of leading reform in family violence, as the newly appointed undersecretary to Justice Minister Andrew Little.

She acknowledged the work of the previous government but did not commit to the future of the ISR.

But one of the first announcements by the new Labour-led Government was an increase in baseline funding - the first in eight years - for family violence organisations like Shine and the Women’s Refuge.

“We do know our crisis services on the ground have been really stretched,” says Logie. “It is so important for them to be properly funded, to spend time with these victims and their children.”

As well as more funding for crisis services and emergency housing, Logie promised putting more money into early identification and prevention.

“How do we help people who are told someone is in a dangerous situation, to help them be safe? This is not just a problem for police. We’ve all got a role to play.

“We’ve known for so long this is a massive problem in this country. And we’ve been sweeping it under the carpet and the problem is getting bigger.”

Other schemes are being trialled, including one where judges are given the entire police history - not just convictions - to help them make bail decisions.

But that’s not enough for the independent Family Violence Death Review Committee, an independent advisory group of experts. Its 2016 annual report urges a fundamental shift in thinking. And a change to the assumption victims can always leave or ask for help.

“Placing responsibility on the victim to achieve safety, when she is unable to keep herself or her children safe, can result in conversations about her poor choices and personal deficits,” says the report.

“This constructs her as the problem – someone who is uncooperative, not wanting help and/or choosing to be abused. Her partner’s responsibility for his abusive behaviour disappears from the picture.”

The reality is that family violence is a form of “social entrapment” aggravated by inequity of gender, poverty and race.

“A number of primary victims in the regional reviews had unaddressed histories of childhood abuse and trauma, and compounding experiences of victimisation throughout their adult life,” it says.

“These victims were extremely vulnerable. They were often grappling with a number of co-occurring issues such as addiction and mental health. Many were in positions of extreme economic disadvantage.

“Māori women are likely to have lower levels of education, be poorer, live in areas with poor quality housing and have their children younger. They are also almost six times more likely to be hospitalised because of assault and attempted homicide, and 1.6 times more likely to die of assault and homicide.”

It’s a passage that could have been written about Marie Harlick.

Jane Drumm, the executive director of domestic abuse agency Shine says Marie Harlick’s death was “absolutely preventable” and is, sadly, a story she has seen many times before.

Drumm says Marie should not be labelled a “bad victim” as opposed to a “good victim”.

Nor should people question why she didn’t leave Hohua, whether or not she was a responsible mother or why she was drinking alcohol.

“We shouldn’t be asking those questions. We should be asking Rob Hohua why he hurt her, terrorised her, and left her children without a mother.”

New Zealanders feel sympathy for children who are abused, often fatally, in dysfunctional homes. Yet when survivors, like Marie, grow into adults, our sympathy is replaced with judgment.

“Yes, they are adults who can make their own choices. And I absolutely believe in individual responsibility,” says Drumm.

“But so often the choices we judge them for, are limited by what they learned when they were little.”

Drumm would spend millions on intensive support for young parents who would otherwise struggle.

Practical help like doing the washing. Finding - and funding - a warm house, so the kids aren’t getting sick. Driving lessons. Childcare. Teaching them how to breastfeed, to cook dinner.

It’s similar to the First 1000 Days philosophy of paediatric specialist Dr Johan Morreau, who believes caring for vulnerable families from pregnancy is the key to reducing our equally shameful child abuse statistics.

Drumm concedes the required level of support would be uncomfortable for many New Zealanders.

“So providing an enormous level of support might be unpalatable. But this is costing us billions of dollars. We have to do something to change it.

“This will get bigger and bigger and bigger. It’s not going away by itself and not doing what it takes to change it will cost us all much more.”

The 36-year-old was this week convicted of murder after a trial at the High Court at Tauranga.

His defence was that he didn’t mean to kill her, ignorant the beating would likely kill her, so was guilty only of manslaughter.

Little of the evidence was disputed; the key issue was what was in Hohua’s mind at the time of the fatal assault.

He sobbed uncontrollably, wailed incoherently in his video interview with police. As this was played to the jury, Hohua cried silently in the dock and fidgeted with his inhaler.

The grief was real, said his lawyer. No doubt true, in part.

But with the guilty verdict, after four hours of deliberation, it seems the jury agreed with the closing comments of the Crown prosecutor Aaron Perkins, Queen’s Counsel.

“Fearsome” was his single word to describe the violence. All because Marie didn’t answer his questions.

“Bear in mind, that’s all she did. Failed to answer him.”

Sitting in the back of Courtroom 3 most days was Vicki Harlick, often too upset to stay and listen to the disturbing details. On hearing the single word “guilty”, she let out a single word: Yes.

Then, thank you, to the jury as they were discharged.

Outside court, the whanau sat around on the steps. Estranged siblings embraced one another. There was no euphoria, just a flat sense of relief.

And playing with her sisters and cousins on the steps was little Vivienne. She turns 3 in March and now lives with her mother’s namesake aunt, Marie Harlick, in Auckland.

Vivienne calls her Nana.

“Justice is served. This was the right result,” said Nana.

"It's just been horrible for everyone ... Now we can concentrate on looking after her daughter, this beautiful little girl."

The verdict is of little consolation to Marie’s daughters. But it means Vicki can fulfil a promise.

Marie is buried in an urupa on a hill in Waihau Bay, where Bay of Plenty meets the Gisborne district.

One side of the burial ground faces scrub-covered hills, a white picket fence keeping long grass and blackberry at arm’s length.

On the other side is the sea. When we visited in August Vicki pointed to a spot where Marie used to swim and teach her children to dive for seafood.

“Mush was awesome at that sort of stuff. She was a beautiful girl … just like this place,” says Vicki.

Marie loved animals too, just like her children. All her daughters are well, says Vicki, especially Vivienne, despite the trauma of witnessing her mother’s death.

“I miss you so much. I just want to let you know, I’m so sorry, I wish I was there,” Vicki tells her sister at the gravesite.

“Next time I’m coming back with some good news, justice for you and for your kids,” says Vicki, resting on the picket fence.

“Then we can put you to rest.”